| Bibliographies and reviews | |||||

| Grading | General works | Biographies | Mixed marriages | Fiction | |

Reviews of fiction related to racial mixture

Chosen laments

Cho / Noguchi Kakuchu on matters of the heart

By William Wetherall

Drafted 19 March 2008

First posted 15 August 2010

Last updated 13 September 2016

Chō / Noguchi Kakuchū

Names

•

Anarchism

•

Marriages and children

•

Naturalization

•

Writing

Chōsen no dōkoku (1953-1)

Former Japanese

•

Chōsen-born Asako

•

Go Heidō and 8th Army Band

•

Mixedblood orphanage

Stories

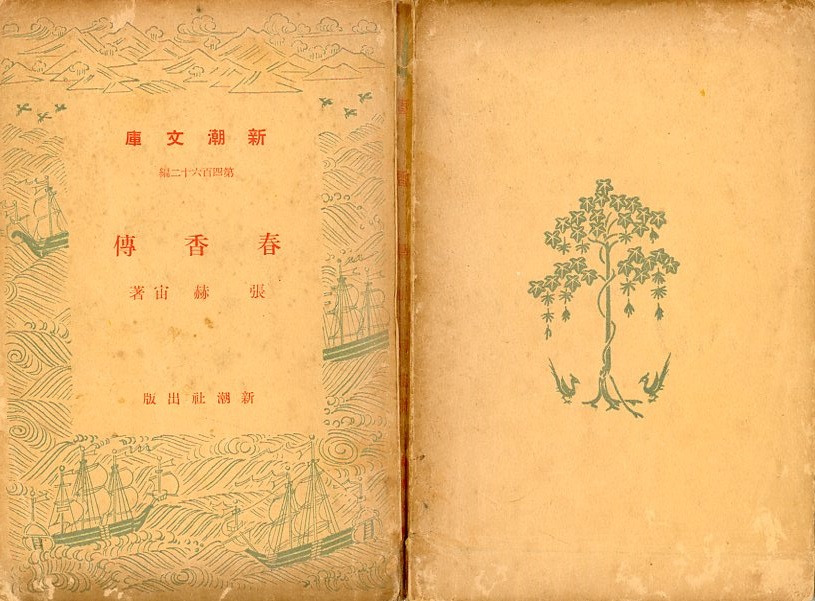

Shunkōden (1938)

•

Yushu jinsei (1938)

•

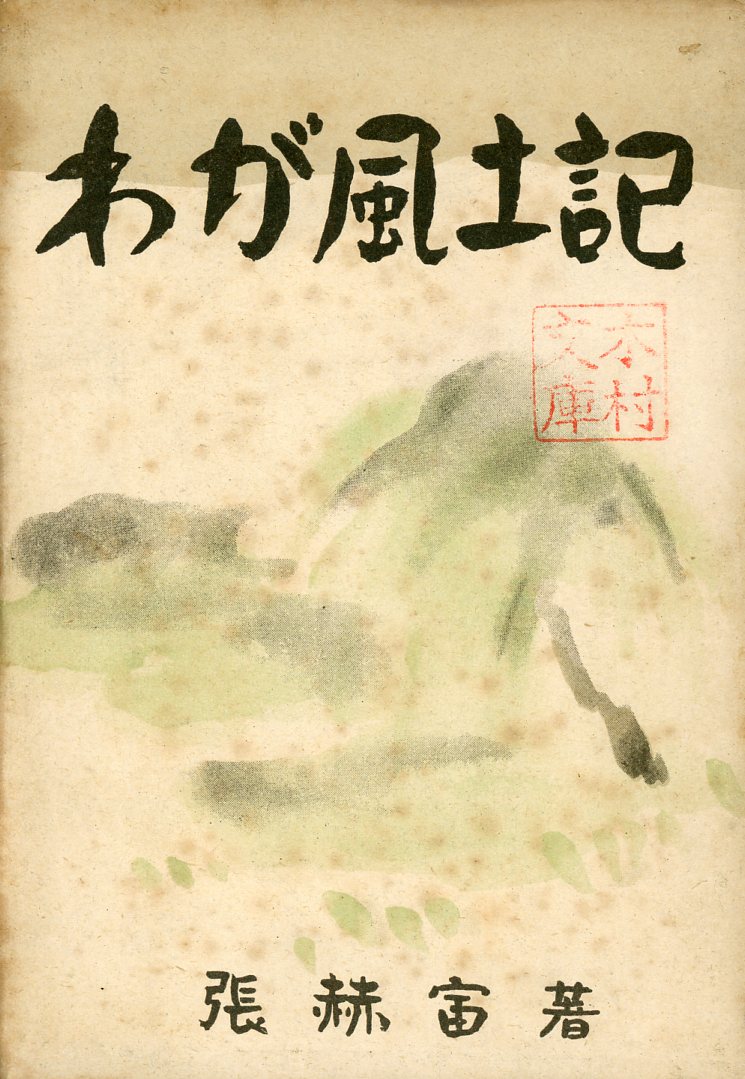

Waga fūdoki (1942)

•

Buraku no nanboku sen (1952-4)

•

Aa Chōsen (1952-5)

•

Aru hanzai (1952-6)

•

Pusan no onna kanchō (1952-12)

•

Kyohaku (1953-3)

•

Masako no baai (1953-8)

•

Henreki no chōsho (1954)

•

Hikage no ko (1956)

•

Izoku no otto (1958-5)

•

Kuroi chitai (1958)

•

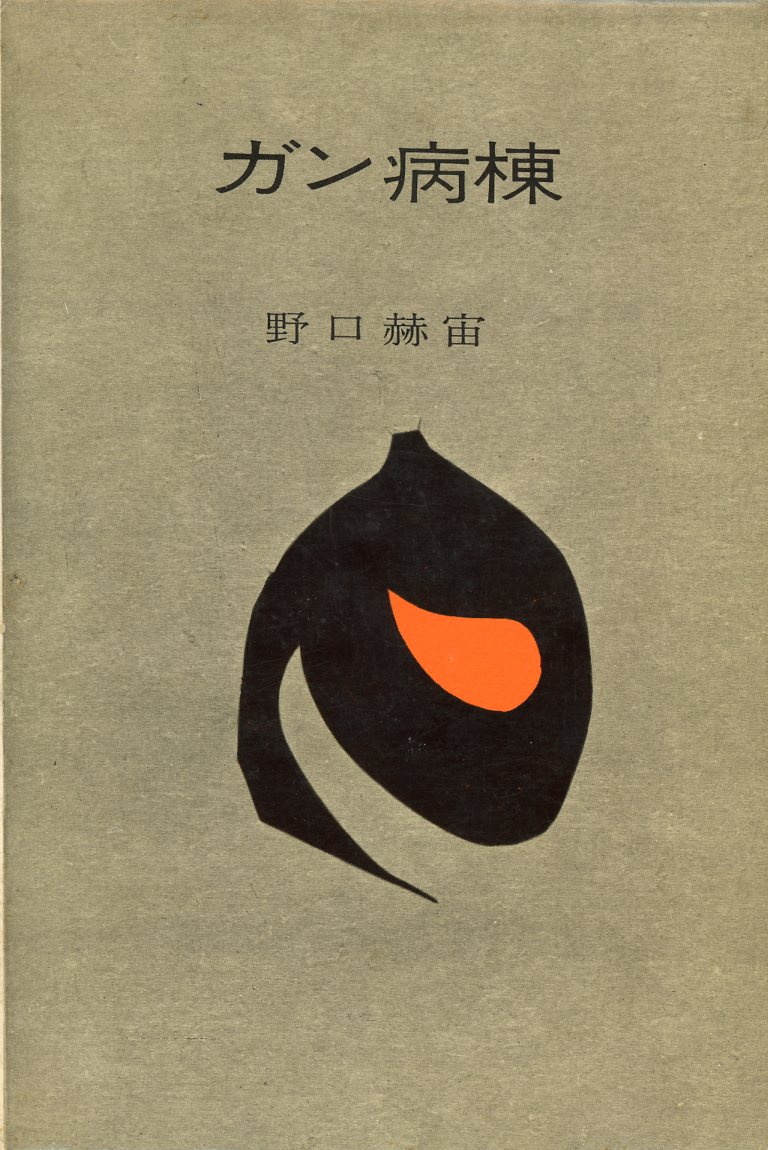

Gan byōtō (1959)

•

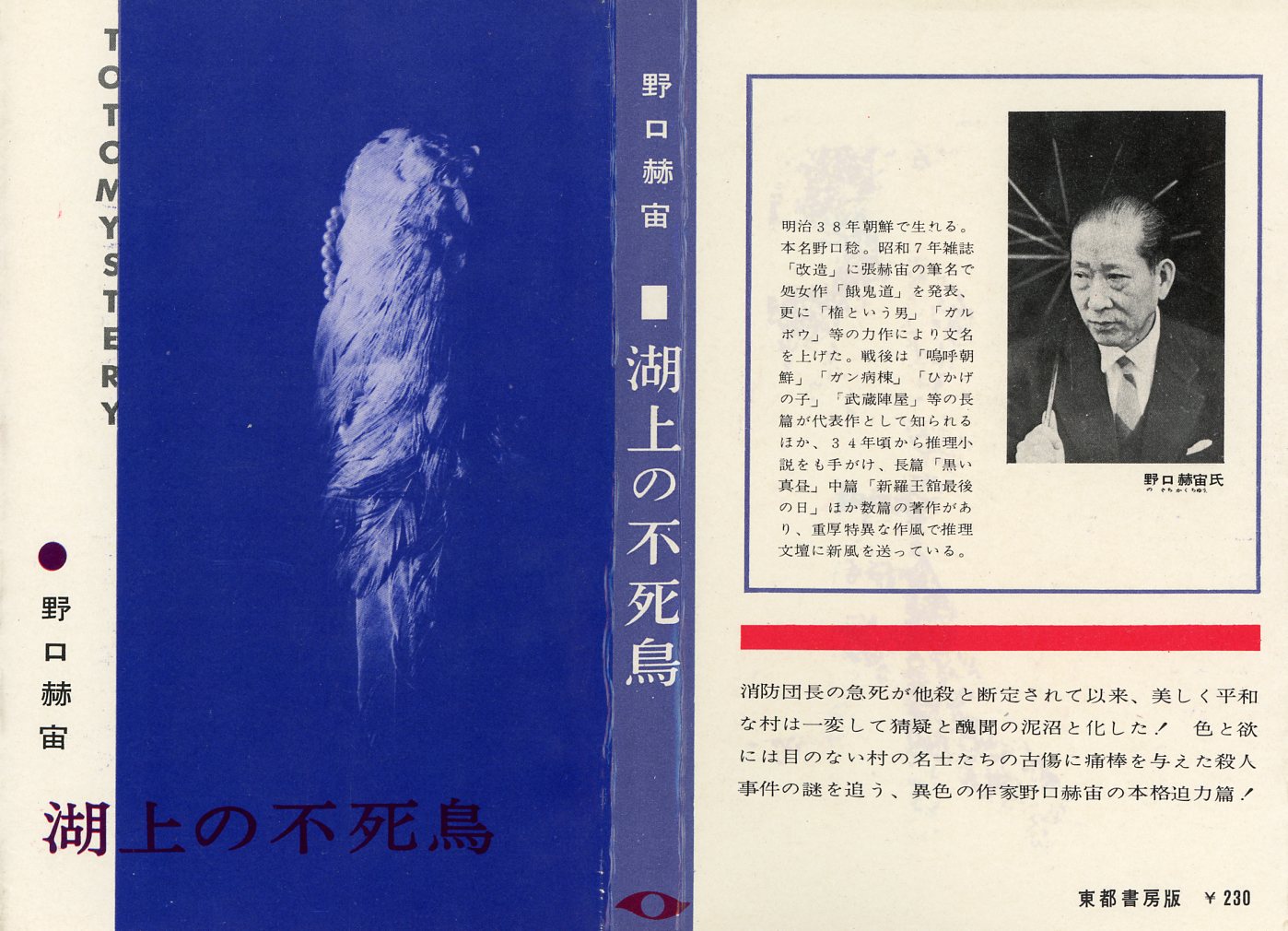

Kojō no fushichō (1962)

Juvenile fiction Wartime titles by Chō Kakuchū, Occupation titles by Noguchi Minoru

History triology

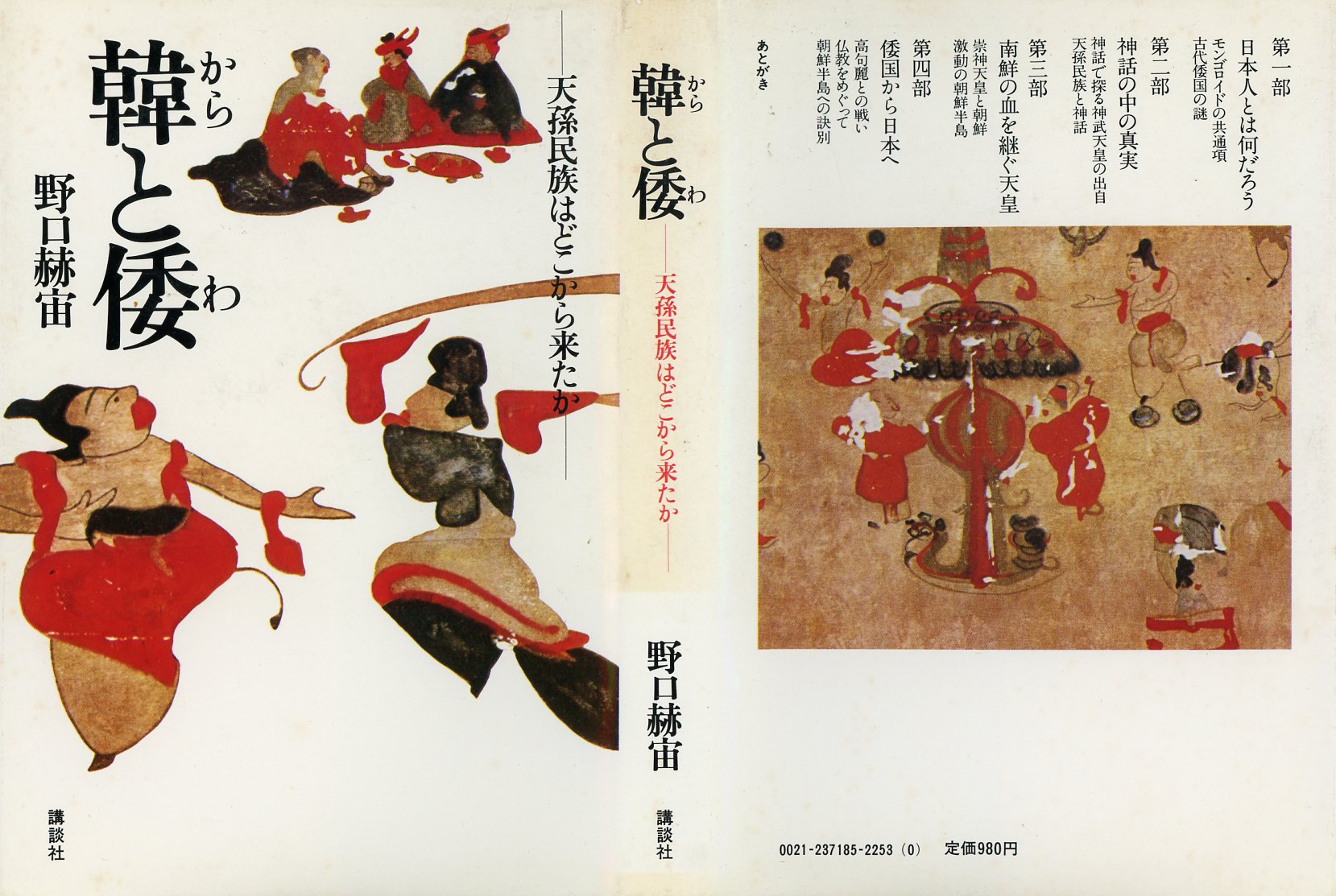

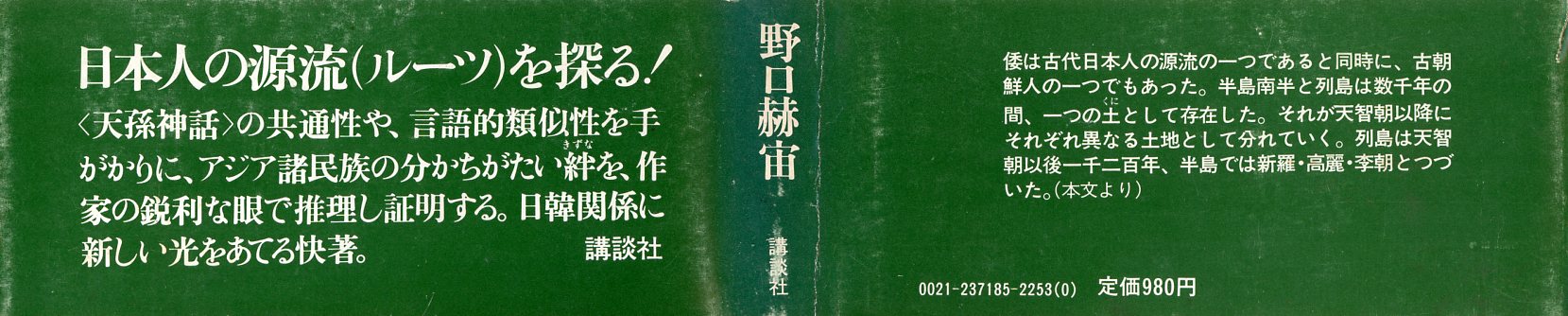

Kara to Wa (1977)

•

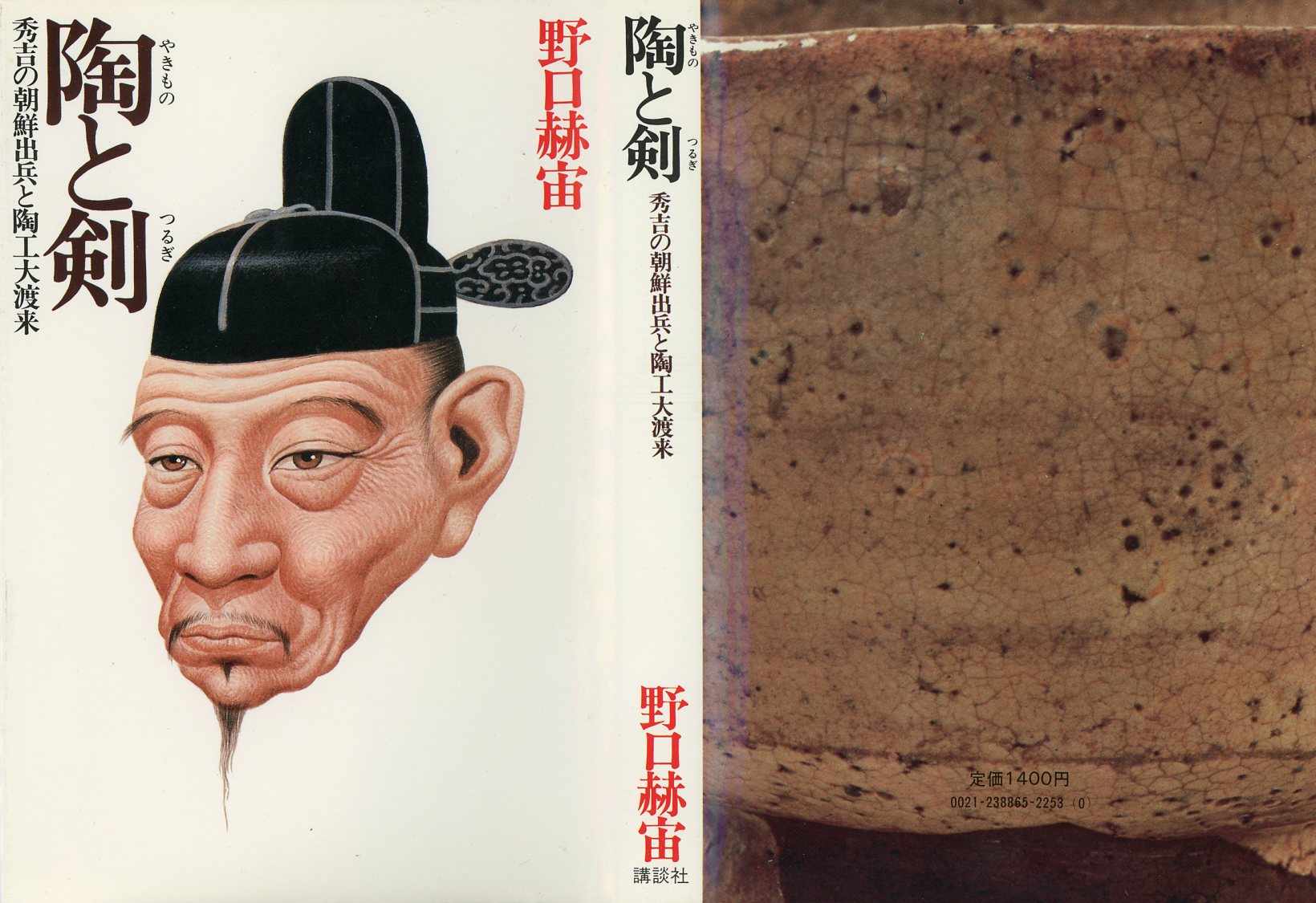

Yakimono to tsurugi (1980)

•

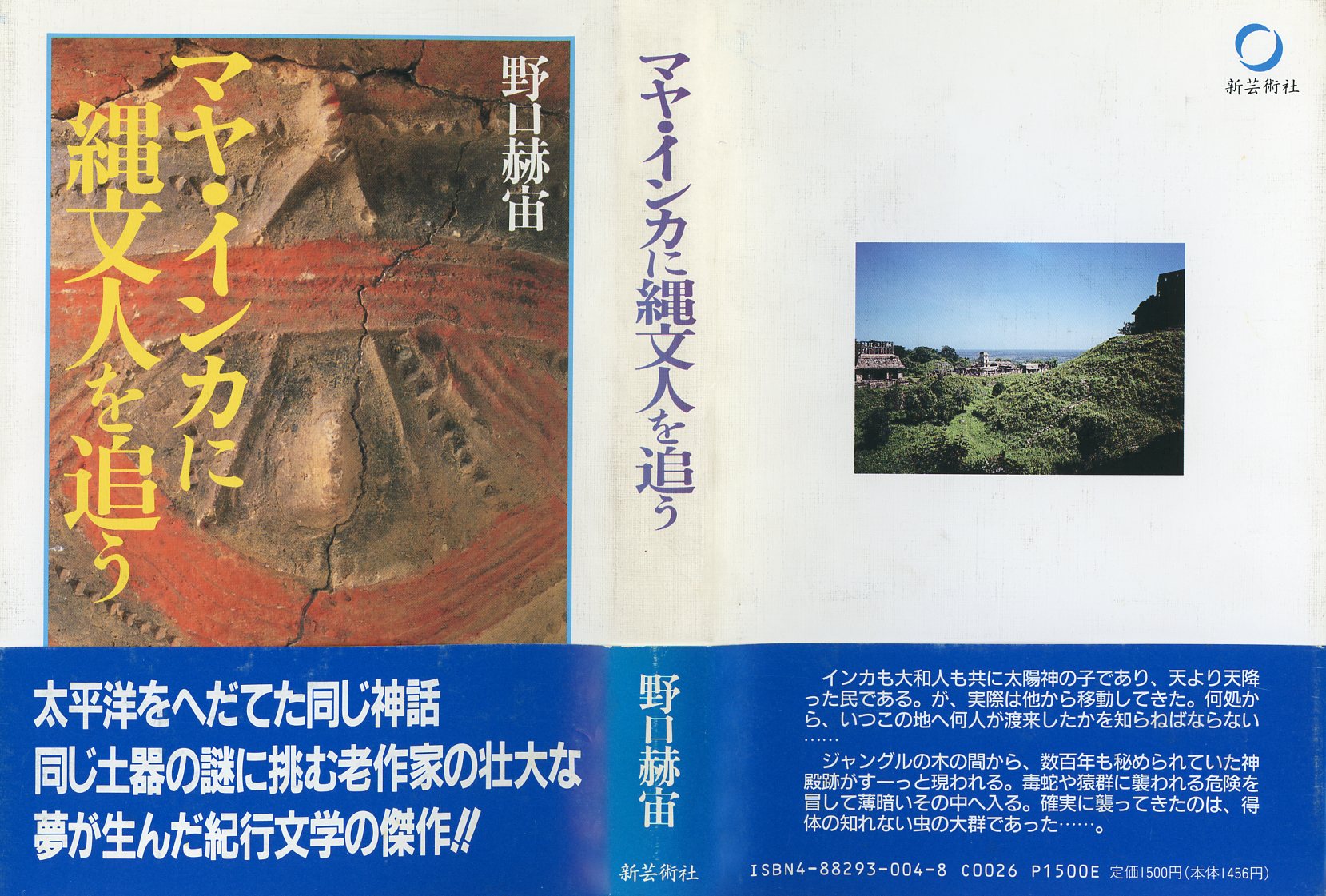

Maya-Inka ni Jōmonjin o ou (1989)

English translations

Forlorn Journey (1991)

•

Rajagriha (1992)

•

Flowers of the Secret Garden (1999)

Selected sources

Kawamura 1993

•

Kawamura 1999

•

Chō (Nan and Shirakawa) 2003

•

Nan 2004

•

Nozaki 2008

•

Shirakawa 2008

•

Kō 2010

John Lie on "Noguchi Minoru" How facts get filtered out of academic "ethnic Korean" advocacy

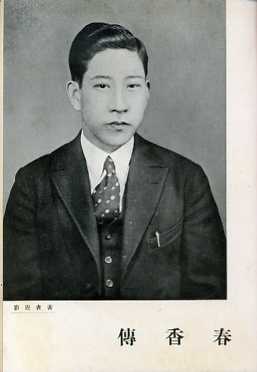

Chō / Noguchi Kakuchū (1905-1997)

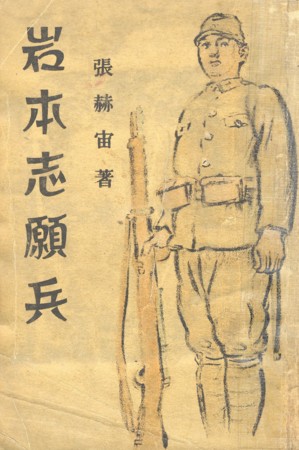

Chō Kakuchū (張赫宙) -- later Noguchi Kakuchū (野口赫宙) -- was born in the Empire of Korea a year after it became a protectorate of Japan for defense purposes, and a month before it also delegated its foreign affairs to Japan. By the late 1920s, already fluent in Japanese, Chō had joined the fashionable anarchist movement. By the early 1930s his fiction was appearing in mainstream Interior magazines. In 1938, a play he wrote the year before was produced in both the Interior and Chōsen, as Korea had become in 1910 before he started school. Chō also wrote juvenile fiction, commentary and reportage, and studies of early history and migration. Most of his works are in Japanese, though some earlier works are in Korean, and late in his life he also wrote in English.

Names

Chō is known by several names, and commentary in Japanese -- and more so in English -- can be both confusing and misleading. Nam Bujin, following Shirakawa Yutaka, describes his names like this (Nam 2003, page 319; structural translation, romanizations, and underscoring mine.

|

In the recent-era literature of Japan and Korea (日韓 Nikkan) there is no personality as unusual as Chō Kaku Chū (張赫宙 ちょうかくちゅう) (1905-1997). He is probably the most symbolic personality the colonial rule of Chōsen by Japan bore [produced and dropped] (産み落とした umiotoshita). As for the real [original] names (本名 honmyō) of Chō Kakuchū, there are Chan Un Jun (張恩重 チャンウンジュン) and Noguchi Minoru (野口稔 のぐちみのる) of [resulting from] creating a family name and a personal name (創氏名 sōshimei); and as pen names, he is a writer who went by the names, before the war, 張赫宙 (in the Chosenese Sinific reading Chan Hyokuchu [チャン・ヒョクチュ]), and after the war mainly Noguchi Kakuchū (野口赫宙 のぐちかくちゅう). He had respectively two Chōsen names and Japanese names, and wrote stories in Japanese and Chosenese, and had Chosen-ality (朝鮮籍 Chōsen-seki) (Chōsen before the war and Korea after the war [戦前の朝鮮と戦後の韓国 senzen no Chōsen to sengo no Kankoku]) and Japan-ality (日本籍 Nihon-seki) Chōsenseki), and led marital lives with a Chosenese woman and a Japanese woman, and in the later years of his long 92-year life continued to write stories even in English. |

Note that katakana チャン -- while phonemically "chan" -- is likely to be phonetically "chanŋ" -- i.e., "chang". Similarly, Nam Bujin writes name in kana as なん ぶじん (Nan Bujin) rather than なむ ぶじん (Namu Bujin), knowing that phonemic "Nan" will most likely assimilate as "Nam" with "Bunjin".

Other variations

There is little evidence, though, that the man who wrote in Japanese as 張赫宙 would have pronounced this byline, at least when speaking Japanese, as other than as ちょうかくちゅう -- which, depending on how the graphs are spaced, becomes either Chō Kakuchū or Chō Kaku Chū. I have adopted the former because it seems to be more common, but the latter would serve just as well.

I have similarly adopted Noguchi Kakuchū when referring to his later works, since romanized forms like "K. Noguchi" appear on weveral colophons. But, again, Noguchi Kaku Chū would serve just as well, and in fact "Kaku Chu Noguchi" is the byline on some English versions of his works.

There are, however, other variations of Chō's name.

Sino-Korean versus Sino-Japanese

The hangul readings of the two Korean-style names, and their McCune-Reischauer romanizations, would be as follows.

張恩重 장은중 Chang Ŭn Jung

張赫宙 장혁주 Chang Hyŏk Chu

Chō, when speaking Chosenese, probably pronounced his names in Sino-Korean, and at times he may have had reason to write these names in hangul rather than graphs. But he appears to have preferred the Sino-Japanese readings of the bylines of the works he wrote in Japanese, as the kana and romanji representations of these bylines reflect Sino-Japanese rather than Sino-Korean.

Post-Occupation name change

Nam's characterization of the variety of names used by Chō Kakuchū is reasonable in terms of understanding that, as a writer, he used this name before switching to Noguchi Kakuchū. However, Nam somewhat muddies the picture by talking about "prewar" and "postwar".

Even if "prewar" is taken to include "wartime" and therefore mean "pre-postwar" -- the "pre-postwar" / "postwar" divide in August / September 1945 does not seem to be an adequate description of the watershed that caused Chō Kakuchū to become Noguchi Kakuchū. It would be more accurate to draw the line between Chō and Noguchi around 1954 -- sometime after the end of the Allied Occupation of Japan on 28 April 1952 -- i.e., after Chō Kakuchū naturalized as Noguchi Minoru.

The author statements on most postwar books and all postwar magazine articles I have examined show Chō Kakuchū (張赫宙) through 1953. Noguchi Kakuchū (野口張赫) appears on publications dated 1954 and later.

Chō published a few works of juvenile fiction in 1949 and 1950 under the name Noguchi Minoru (野口実). Note that this is graphically different from the Noguchi Minoru (野口稔) he became when naturalizing in 1952, but there appears to be a reason for this (see "Sources" below).

Nam's characterizations of "Noguchi Minoru" (野口稔) as the result of "creating a family name and a personal name", and of Chō's "Chosen-ality" and "Japan-ality", are also require comment (see "Chō's Kakuchū's naturalization as Noguchi Minoru" below).

Anarchism

Like many writers at the time, Chō flirted with agrarianist and proletarian thought, but denied he was a Marxist. He never entirely abandoned his interest in the poorer underclasses, which is clear in his generally humanistic writing about the struggles and sufferings of ordinary people.

By the late 1930s Chō had begun writing articles that resonated with Japan's efforts to totally assimilate Chosenese people into the Japanese mainstream. In 1939 he wrote a series of articles for Bungei, a mainstream Interior literary magazine, to the effect that the Chosenese language was limited and dying, and Japanese provided more opportunites to be translated into foreign languages. This caused him to be ostracized in both Chōsen and the Interior by Chosenese literati who saw writing in Chosenese as essential to being Korean or Chosenese.

During the early 1940s, Chō made a number of trips to northern China and Manchuria, from which he reported on developments there. During World War II he wrote a number of novels that mostly portrayed Japan's activities in Chōsen and Manchoukuo in a favorable light. He was on an assignment in Chientao and northern China in 1945 when his Tokyo home was destroyed in an air raid. Japan surrendered soon after he returned to the Interior, where he evacuated to Nagano with his family there.

Marriages and children

Shortly after graduating in March 1919 from what today would be middle school, Chō was married to Kim Kwihaeng (金貴行 김귀행), apparently in accordance with the custom at the time of early marriage. He and Kim went on to have three sons and three daughters (Shirakawa Yutaka, in Chō 2003, page 338).

Another account gives 1920 as the year in which he and Kim were married (Shirakawa 2008, page 258). He also began to study English this year, and in the fall of 1921 he was baptized as a Presbyterian. The same account says his second son Sŏwan (性元) was born in October 1930. No mention is made in this account of the other children he had with Kim. She is said to have died, however, "by 1948" (Shirakawa 2008, page 24).

Chō made his first trip to the Interior in 1926, and he made a number of other trips, mostly to Tokyo, before beginning to live there in 1936 (Shirakawa 2008, page 258).

In June 1936 he went to Tokyo intending to reside for a few months. In spring the following year he met Kim Saryang (金史良), who was studying German at Tokyo Imperial University. In early summer he became close to Noguchi Hanako (野口はな子), who went by the name Keiko (桂子), and who had taken care of him when he was sick. She is said to have been the daughter of a relative relative of the landlord of the lodging house where he was residing, who had come to work as helper. Later that summer they began living together at Kamisuwa in Nagano prefecture. Later they married, and they had five sons. (Shirakawa Yutaka, in Chō 2003, page 339.)

Another account says he met Noguchi Hanako in 1932 (Shirakawa 2008, page 259). This account, which goes only as far as 1942, says of the first three of five sons born to him by Noguchi (Shirakawa 2008, page 25), that Kakuo (赫男) was born on 19 October 1938, Yoshio (嘉男) was born on 30 June 1940, and Haruo (治男) was born on 17 March 1942. This account also states that Chō "This year, does create-family-name change-personal-name" (この年、創氏改名する Kono toshi, sōshi kaimei suru) (ibid, page 259).

Noguchi Kakuo (野口赫男) is presently one of two full-time auditors at at Nihon an Nihon Jūtaku Butsuryū Sentaa, a housing industry distributor and wholesaler, having begun his career in the building supply industry at Nishō Iwao in April 1962, when he would have 23 years old and presumably fresh out of college.

On 25 May 1945, while he was in Manchuria and Northern China, his Tokyo home was destroyed in an air raid. When he returned to the Interior in August, he lived in an evacuation camp in Hirooka village in Nagano. By 1947 he had resettled in Hidaka town, now Hidaka city, in Saitama prefecture. (Shirakawa Yutaka, in Chō 2003, page 340.)

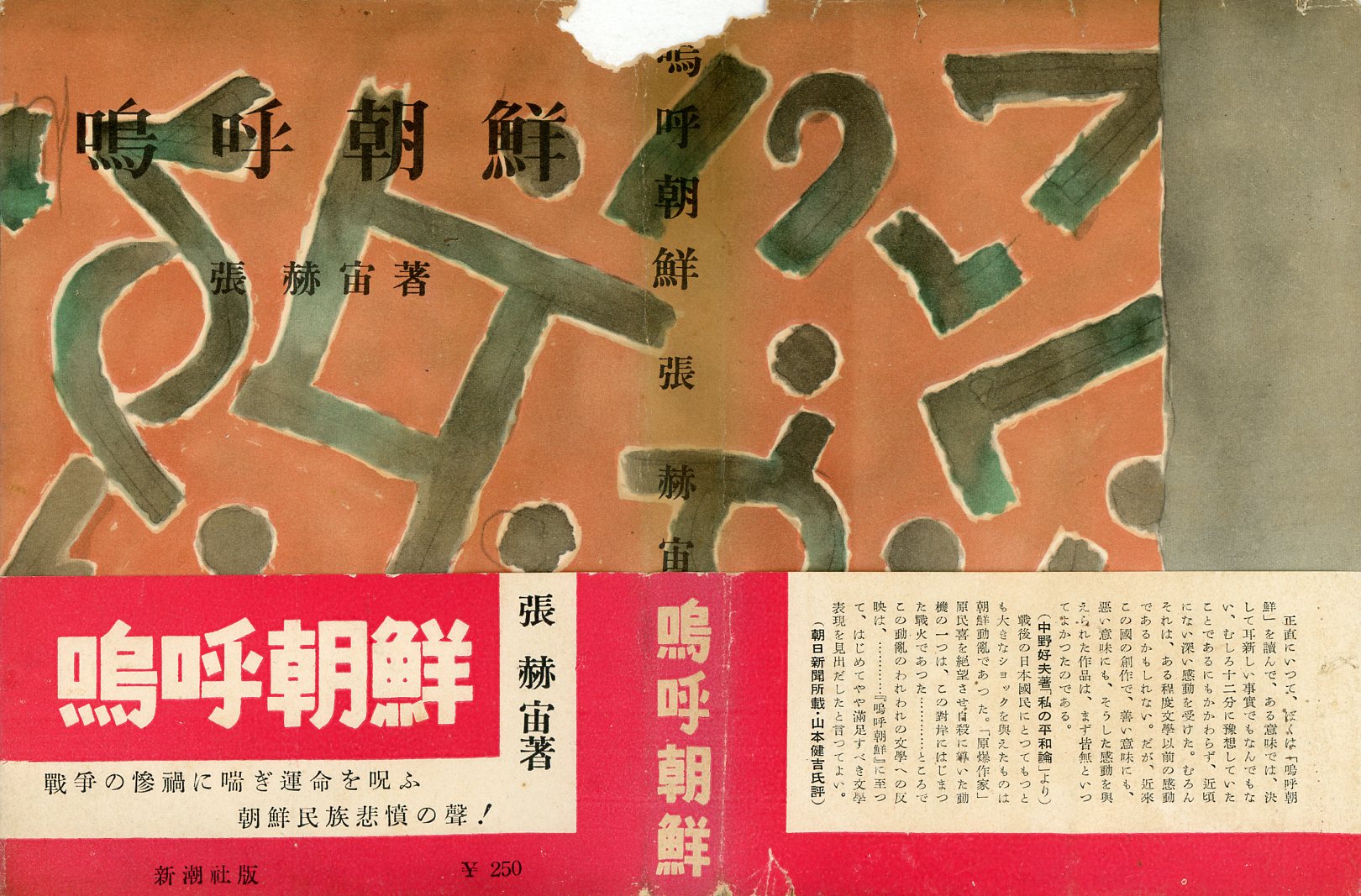

In July 1951 he flew to Chōsen (朝鮮) on an American military aircraft, to report on the Chōsen War (朝鮮戦争), with the support of the Mainichi News Company (毎日新聞社). In May 1952, he published the full-length novel Aa Chōsen (Shinchōsha) with the writing name (筆名) Chō Kakuchū. In August 1952 he again went to Chōsen, and the same month he applied for naturalization in Japan and became Noguchi Minoru (日本に帰化申請し、野口稔となる Nihon ni kika shinsei shi, Noguchi Minoru to naru), and as a pen name (ペンネーム) uses Noguchi Kakuchū et cetera. (Shirakawa Yutaka, in Chō 2003, pages 340-341.)

Chō's motivation for going to Korea in 1951 appears to have included the desire to confirm the safety of the children from his marriage in Chōsen. Of interest here is that, according to my research, shortly before the publication of Aa Chōsen he published a short story called "Buraku no nanboku sen" [North-south war of villages] -- featuring a man who had migrated to the Interior from Chōsen, leaving his family and a woman he was not allowed to marry in a part of the peninsula that had been twice been overrun by armies during the early months of the war -- and had come to see what had become of their villages (see below).

Chō's October 1952 return gave him the extremely interesting material for "Chōsen no dōkoku" [Laments of Chōsen], the January 1953 reportage I am introducing here (see below). The article epitomizes Chō's passionate and sympathetic regard for the plight of racially mixed couples and children. The article mentions facts which he had worked into a "Pusan no onna kanchō" [Female spy in Pusan], fictional story he published in December 1952 (see below).

Nam Bunjin examined a number of Chō's pre-postwar stories, and also some stories by Kim Saryang, with respect to the them of "Interior-Chōsen marriages" in literature. Nam sometimes mars his analyses of historical literature with present-day "multiculturalist" and "multiethnic" commentary. And he is inclined, like may scholars to adopt a "critical" view of the imperial years, to warp contemporary Chōsen, Chosenese, Interior, and Interiorite metaphors into Korea, Koreans, Japan, and Japanese.

Yet Nam's review of the theme of mixture is a welcome and valuable contribution to an understanding of a truth that most scholars seem to disregard in their rush to racialize Koreans that remained in Occupied Japan after World War II. "Koreans in Japan" as of 1945 have to be understood as a very humanly complex population of migrants from Chōsen who had settled and assimilated in the Interior, and their native-born descendants, and people people who as Interiorites had married or been adopted into Chōsen registers, and in- and out-of-wedlock children of legal and commonlaw marriages and other relationships between Interiorites and Chosenese men and women.

Naturalization

Chō's Kakuchū's naturalization as Noguchi Minoru

Nam's characterization of "Noguchi Minoru" as a consequence of "creating a family name and a personal name" (創氏名) is odd at best -- and Shirakawa Yutaka's allegation that Chō's Kakuchū "applied for naturalization in Japan and became Noguchi Minoru" (日本に帰化申請し、野口稔となる) in October 1952 also scores low on a scale of clarity and accuracy.

Both Nam and Yoshikawa fail to mention that Chō had become Japanese when Korea was annexed as Chōsen, and he remained Japanese until 28 April 1952. On this date, as an effect of the San Francisco Peace Treaty, Korea (Chosen) and Formosa (Taiwan) were separated from Japan. And as an effect of the separation of these territories from Japan, Chosenese and Taiwanese -- meaning people in Chōsen and Taiwan territorial registers -- lost their Japanese nationality.

Chō trip to Korea as a correspondent on a US military flight in July 1951 had to have been with the understanding of GHQ/SCAP that he was domiciled in Japan and would not lose his legal status as a domiciled Korean (Chosenese) with Japanese nationality. He could not have applied for naturalization until losing his Japanese nationality in April 1952. And despite his fame, it would have taken a few weeks to expedite, but more likely several months to normally process an application for permission to naturalize.

If in fact Chō naturalized in October 1952, permission would have been granted, and notification of the grant of permission would have made in the National Gazette, around that time, after which he would have been entered in a municipal family register and become, again, Japanese. There remains, however, the riddle of when he legally married Noguchi Hanako.

Under Chōsen and Interior laws, marriage to an Interior woman while married to a Chōsen woman, or vice versa, would have been considered polygamy. When did he divorce Kim and marry Noguchi? Divorce would have been extremely difficult after Japan's surrender, when communication between Interior and Chōsen registrars regarding private household register (family) matters ceased.

Had Chō married Noguchi before the end of the war, she would ordinarily have been registered in his Chōsen register as his wife. Even had they married in Occupied Japan before the 1950 Nationality Law came into effect, under legacy Chōsen and Interior laws still in effect in postwar Japan, she would probably have migrated to the copy of his Chōsen register maintained at the municipality in Japan where they resided. And upon entering his register, she would have become Chosenese and hence lost her Japanese nationality when he lost his.

If, however, they married after the 1950 Nationality Law came into effect, she would have remained in her Interior register as Noguchi Hanako. And when he naturalized, he would probably have entered her register as her husband, and thereby assumed the same family name.

Another possibility is that Chō divorced Kim sometime shortly after taking up with Noguchi. She would have removed from Chō's register, and either returned to her natal household register if the head of household (her father or a brother who had succeeded her father) accepted her, or been given her own family register. If Chō had then married Noguchi, then under interterritorial laws, most likely she would have migrated to his Chōsen register and taken his name family name, rather than he migrate to her register as an adopted husband and assume her family name.

If Noguchi had entered Chō's register, then after the Chōsen Government General create-family-name, change-personal-name decrees of 1939 came into effect in 1940, Chō might have adopted the name Noguchi Minoru in his Chōsen register. But this scenario does not seem likely, since Chō appears to have totally settled in the Interior, where he continued to be known as Chō Kakuchu. And obviously he did not become an adopted husband in Noguchi's Interior register, had he been in an Interior register in 1952, Chōsen was formally separated from Japan, he would have remained Japanese.

If Noguchi Hanako had become Chosenese and as such lost her Japanese nationality in 1952, then the children she bore with Chō would have also become Chosenese and lost their nationality. And if this were the case, then both she and Chō, and their children, who were still minors, would have had to naturalize as a family.

All this is speculation. Some of the Noguchi sons must still be alive. Presumably there are copies, somewhere, of the older registers showing the status acts of concern here -- the marriage of their parents, and the naturalization of at least their father. The notification in the Official Gazette would also show who was permitted to naturalize as of the date of the notification.

One thing is certain, though. Nam's claim that "Chosen-ality" (朝鮮籍) was "Chōsen" before the war and "Korea" after the war is contrary to the facts of Japanese law. "Chōsen" remained "Chōsen" in Japanese law after the war and throughout the Occupation, was "Chōsen" in the Japanese version of the 1952 San Francisco Peace Treaty, was "Chōsen" in the Japanese version of 1965 ROK-Japan normalization treaty, and remains "Chōsen" today as the affiliation of aliens in Japan who continue to be classified as members of Chōsen registers (Chōsen-seki 朝鮮籍) in lieu of having a "honseki" or "nationality" in a recognized state. As a legacy status status today, "Chosen-ality" is a nationality without a state, hence people of legacy Chosenese status in Japan are de facto stateless aliens. In most government statistics, they are conflated with nationals of the Republic of Korea, which is a recognized state. ROK nationals regard themselves as being of "Korean-ality" (韓国籍), hence (I presume) Nam's impulses to "Koreanize" Chōsen and Chosenese.

Of greater interest, though, is the fact that, whenever and whyever Chō Kakuchū became Noguchi Minoru, he seems to have (1) continued to write as Chō Kakuchū for at least a year after he had become Noguchi Minoru, and (2) even after abandoning Chō for Noguchi, he continued to use Kakuchū -- presumably because he liked the name and was proud of the name -- until his death.

Writing

Chō had long been interested in history, however, and in 1977, at the height of one of several booms of interest in the origins of the Yamato racioethnic nation, he wrote a book, as Noguchi Minoru, about ancient "Kara" (Korea) and "Wa" (Yamato).

Chō conceived four volumes in English writing as Kaku Chu Noguchi. One volume, set in the Tokugawa period, was published in 1991 under the title Forlorn Journey and the name Kaku Chu Noguchi. A Japanese version was to be called "Hatashie naki tabiji" (果てし無き旅路).

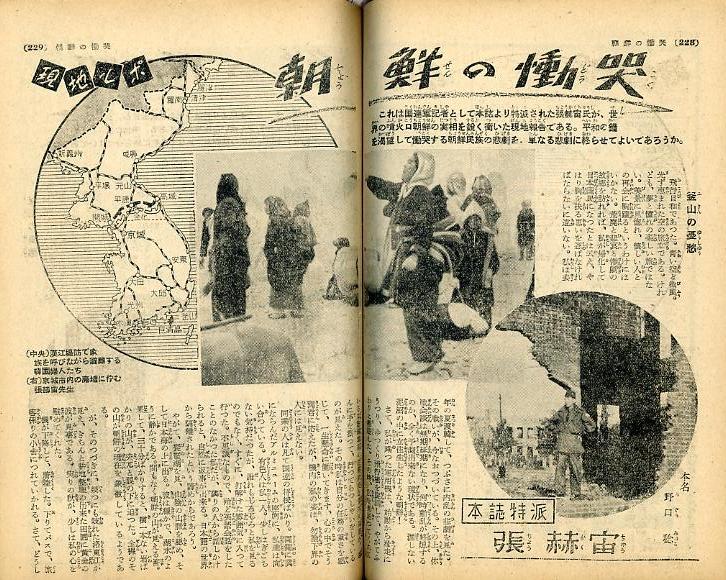

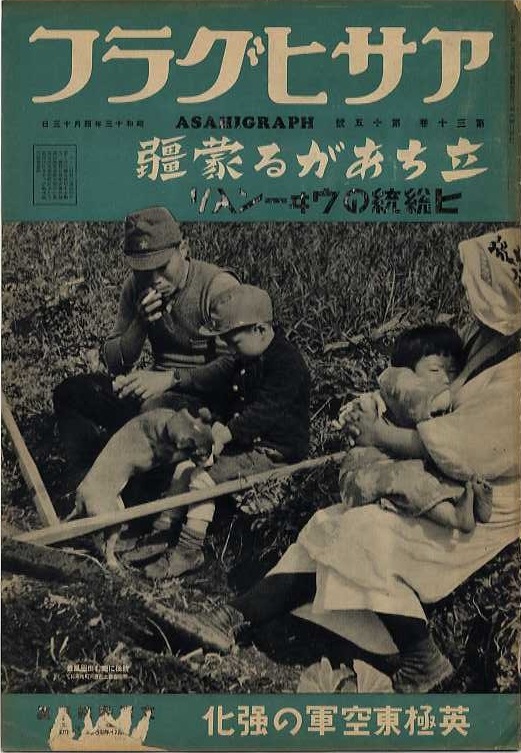

Genchi rupo: Chōsen no dōkokuChō Kakuchū 1953-1現地ルポ:朝鮮の慟哭 Genchi rupo: Chōsen no dōkoku Chō Kakuchū's byline appeared in numerous popular and literary monthly magazines in the months after the Occupation of Japan. Hardly a month passes in 1952 and 1953 that an article by him -- writing as Chō Kakuchū -- did not appear in a major monthly. Some reports, and an entire book, were based on observations during two trips he made to the peninsula as a journalist during the Korean War. The dateline of this article is "Keijō, 25 October 1952" (昭和二十七年十月二十五日京城にて). The article shows a number of photographs, of refugees with children, of orphans, of Go Heido and Aiko (see below), and of Chō himself in the military uniform he wore as a correspondent at a market in Keijō (Seoul), with orphans at an orphanage, and with women of the night, among others graphic evidence of the war. The following article by Chō Kakuchū is one I discovered while thumbing through the January 1953 issue of Fujin Kurabu, which I had bought because it had materials related to Shishi Bunroku and Wanibuchi Haruko. Shishi as a father, translator, and novelist -- and Wanibuchi as a child, violinist, and model -- figured in work I was doing on mixed-blood people born in Japan before the end of World War II. Chō's article, it turned out, was about mixture related to Korea -- couples as well as children born to married parents and out of wedlock. Reporting from Korea during the Korean War, the couples and children he met spanned the period that Korea was part of Japan. Chō's article turned out to be one of the most interesting eye-witness accounts I have seen from a seasoned writer with the skills of both a journalist and a novelist -- and someone who, from his own experiences, deeply understood matters of the heart, romantic and patriotic. 張赫宙 (本誌特派) Chō Kakuchū (Honshi tokuha) [This magazine's special dispatch] 婦人倶楽部 Fujin kurabu lead-inThe lead-in below the headline sets the hook like this.

The January 1953 issue was compiled, published, and distributed in late 1952. Cho had gone to Korea as Noguchi Minoru, a Japanese reporter. It is not a guise, for in October he had naturalized to reacquire the Japanese nationality he had lost on 28 April that year. So US military personnel in charge of facilitating journalists knew him as Noguchi. Cho, decked out in military fatiques and a garrison cap, with all the proper markings that identified him as a reporter, trapsed over the war zone south of the frontline, which snaked north and south of the 38th parallel but had by then become fairly stagnant, to explore every facet of life and death in the UN war zone -- the vast displacement of people and destruction of property, POWs, refugees, orphans, women of the night, Japan wives, mixed blood children. He speaks enough English to get around with American soldiers. He switches to his native Korean and virtually native Japanese when necessary. |

Former Japanese

He goes by boat from Pusan to Kojedo, where most DPRK and PRC captives are being held in a variety of POW camps. In May that year, some of the camps rioted, and for a while the general in charge of the camps had himself become a captive. This exposed not only the lack of security, but also the poor conditions, which captives had exploited with the help of sympathizers outside the camps. Administrators were now going out of their way to accommodate the world press corps, to publicize how much control over the camps, and conditions within the camps, had improved.

In the Korean camps, Cho sees Koreans who differ from the armed Koreans guarding the camps only in their garb. He writes that his heart has become Japanese, very far from a Korean heart, and already his eyes have taken the position of a third party. It makes no sense to him that "same wombers and same causers" [(racioethnic, national) sibling comrades] (同胞同志 dōhō dōshi) should be fighting each other. It pains him to see the divide between them. (Page 236)

Between the camps are flower and vegetable fields. On the right of the road he sees people's houses (民家 minka) but not a single hamlet person [villager] (部落民 burakumin). He has heard on the boat that they had been forced to evacuate and had moved to a different hamlet (部落 buraku). The evaluation was carried out to prevent secret liasons with the captives. (Page 236).

One of the POW camps is full of women. They are dressed like men but are women. Most are in their teens. Few are adults. A woman around twenty approaches the barbed wire and looking at him starts shouting "Yai, Waem!" [倭奴 (日本人め) ウエーム (にほんじんめ) Ueemu (Nihonjin-me)] -- meaning "Hey, Jap!" He reports "Her face shows hatred, hostility, and displeasure. It is ugly. But, for me that on the contrary made me feel the sorrow [sadness] of humans." (Page 237)

Next he sees a camp which has only children and at first glance looks like a kindergarten. Surprised, he asks his military guide what it is. The US Army Major says they are children who accompanied their captive mothers. Cho looks away, his feelings unbearable. He has never heard of such a camp.

The next morning he encounters a few Japanese women working on a ship that had docked at a wharf in Pusan. They were dressed in greasy pants and wore what looked like UN forces fatigue jackets, and at first he thought they were men. But on closer inspection he realized they were Japanese.

The women had lost their husbands and were hiring out for work on ships while living in Shōrinji (小林寺), a temple in Pusan that was sheltering former Japanese (元日本人 moto Nihonjin). At the end of the [Pacific] war, the temple had become a shelter (収容所 shūyōjo, accommodation place, holding camp) for withdrawing [evacuating, repatriating] Japanese (引揚日本人 hikiage Nihonjin). With the upheaval [on the peninsula], it again became a Japanese shelter (日本人収容所 Nihonjin shūyōjo).

The women were living with their children in the main hall of the temple and an adjoining building. The ROK government was giving them a daily ration of rice, but the women had to rely on their own resources for other things they needed to maintain their lives.

Cho continues in this vein (page 237).

|

It may be my personal emotions, but the despair of these women, having come from a distant different country, and lost their beloved husband in death, was far more serious than [that of] Korea wives (韓国婦人 Kankoku fujin), and more grievous [sorrowful, touching]. These wives too could speak Korean well. Among them were women [who had been speaking] Korean so one-sidely that they are forgetting Japanese. However, the hearts of these women are always turned toward Japan, and in their dreams their hope of returning to Japan is never abandoned. It is sorrowful. I went to the side of a woman who was cooking, and spoke. "I came from Tokyo. I'm a correspondent for Fujin Kurabu." "Fujin Kurabu? Ah, that brings back memories." [With] her sunburned face, [she] could be mistaken for a man. [She] probably had no margin [could not afford] to use cream or white powder (クリームも白粉も kuriimu mo oshiroi mo). |

Cho reveals, through further conversation with the women, that she was from Kyoto, her husband had died of illness, and she had taken the work on the ship because she had nothing to eat.

Another woman he interviewed had been living in Keijo (Seoul) when the war began. Her husband had been killed by the People's Army because he had been an official of Korea (韓国 Kankoku). He had hidden under the floor of their home but a neighbor exposed him.

Yet another woman and her husband had been running an eatery in North Korea [Northern Chōsen] (北鮮 Hokusen). The People's Army [of DPRK] had taken her husband with them when it retreated [north from UN forces during the first UN offensive]. Convinced he would be killed, she accompanied UN forces when they retreated [south from Chinese communist forces]. She had left two children with an acquaitance [at at undisclosed location].

Cho, running out of time, bid the women farewell. The one he had given a copy of Fujin Kurabu looked forlorn as she watched him leave. She clutched the magazine as though it were precious. He waved at her. She raised a small hand and weakly waved back.

Chōsen-born Asako

Cho encounters a number of Japanese or former Japanese during his tour. In Keijo (Seoul) Cho hears about a Japanese woman who fears people knowing that she is Japanese. He arms himself with a copy of Fujin Kurabu and sets off with his driver to find her. He writes that, if she is Japanese, she will see the magazine, feel nostalgia, and want to meet him.

As predicted, she responds pretty much as others had when seeing a magazine that brought back fond memories -- except that her Japanese is mixed with Korean, which Cho faithfully records in his dramatization of the encounter. The woman invites him into her house. She has been making futon in preparation for winter. She spreads a blanket for him to sit on, and all but takes his hand, she is so delighted to meet him. (Pages 240-241)

He tells her he had come from Tokyo, and she gives the address of her own Tokyo register and her father's name, which Cho records in the article (page 241).

|

"My name, because I was born in Chōsen (朝鮮), is Asako (朝子)." Her Japanese is gradually getting better. "The day I was born is 23 February 1929." "Why don't you withdraw [repatriate] to Japan?" "Aigo (Oh), can I return to Japan?" "You can return. If you go to Pusan, there's a place called Shōrinji . . ." I explained. But she couldn't if there was no one to receive her.

|

The drama continues. The woman's father is dead. Her mother had long ago remarried. She was alone. She had married a police officer of Korea. He had been killed in the Yosu incident (麗水事件 Yosu jiken).

|

Yosu incident In late October 1948, thousands of people in the town of Yeosu (Yŏsu) and its vicinity were killed when ROK forces supressed a local insurrection, related to insurrections on Jejudo and elsewhere, motivated by discontent with ROK's claim that its government, founded on 15 August, was the sole legitimate government of the entire peninsula, thus disregarding the voice of supporters of the government of DPRK, which founded on 9 September. |

Asako was rescued from her hunger by a newspaper reporter who turned out to have a wife and child. She doesn't get along with his wife, goes to Pusan, and sees the foreign soldiers. She could eat if were lean on them. But how to get close? She uses her heart (心をつかつて koro o tuskatte) [emphasis in original] -- from which, she says, she "went into this business". She is embassed, ashamed, of these developments, and the fact that she has even begun to forget her Japanese. She breaks down. Cho himself is moved to tears. (Page 241).

Compounding the pains of life and the agonies of race, and her own misfortunes and the atrocities of war, which had left Asako stranded in Korea with no hope of going to Japan, is yet another development. At the time Cho met her near Keijo, she had a UN soldier patron. And she worried that, if she didn't serve him as best she could, to pull a hundred-dollars a month from him, she would loose him to another woman. (Pages 241-242)

"I hadn't felt like talking to women of this sort in Japan," Cho writes, "but Senoo Asako didn't have a dirty [squalid] feeling about her, and I could not forbid [myself] a sense of deep sympathy." (page 242).

Asako told Cho of a place where about forty Japan wives were living with a lot of children. He drove around but was unable to find it.

Go Heidō and the 8th Army Band

Cho spoke of the "tragedy" of international marriages (国際結婚 kokusai kekkon) in terms of "misery" (page 238) and "collapse" (page 242). Bright stories were few, he writes, but the families of some Japan-Korea marriage were leading very happy lives (page 242).

One such family was that of Go Heidō (呉炳道), a flutist in the 8th US Army Band [which had participated in most Korean War campaigns]. Many people in Japan knew him as a member of the former BK Band. His wife's real name (本名 honmyō) was Sakamoto Aiko. She was 31, and her principle register was in Tokyo. Cho gives the register address (as he does with other such addresses in the article) down to the banchi, and even the names of her younger sister and brother. He then makes this observation (page 242).

|

[The two] are residing with [their] three children in an upper stream [higher class] home, and [it] is an appearance of harmony that would be enviable to an outside eye. The love of the two that had transcended [ethnonational] nation [race] (民族を超越した二人の愛情 minzoku o chōetsu shita futari no aijō), had come to surmount the hardships [of the Korean war]. |

But Aiko is wary of anti-Japanese associations, and she doesn't venture out on National Jubilation Commemoration Day [on 15 August, when ROK nationals would celebrate both the liberation of Korea from Japanese rule in 1945 and the founding of ROK in 1948].

The article features a picture of Go and Aiko surrounded by their three children. They are sitting on the floor and smiling as Go, in uniform, shows a copy of Fujin Kurabu to the oldest daughter, who is looking is looking down at the cover as though to wonder why all the fuss. (Page 240)

Mixed-blood orphanage

Then comes the shorter but sadder final sections on the loss of morals that inevitably accompany struggles to survive, a camp full of children orphaned by the war, and mixed blood children. There is a picture of Cho with a six-year-old girl and her younger brother. An American soldier had spotted her, wandering around a battlezone where bullets were flying, with a two-year-old infant on her back, and holding the hand of her brother, who was walking beside her. They were brought to Seoul, and admitted to the orphanage, but the baby brother, who had come down with typhoid fever, had been moved to another facility and later died.

Next came a short section entitled "Mixed-blood orphanage" (混血孤児院), about which Cho says this (page 344).

|

[The compound miseries of the war between same-wombers and same-causers] was a sadness peculiar to Korea (韓国 Kankoku), but it had an agony entirely in commmon with Japan. The problem of mixed-blood children (混血児の問題 konketsuji no mondai). The orphans who had born from ignorance toward pregnancy, and carelessness, [on the part] of the women of the night, and [then] abandoned! The white kids and black kids, none were born of their own will. At an orphanage at the foot of Namsan, thirteen mixed-blood babies are being sheltered (accommodated). Babies of a pale ink-color, are opening their big mouths and wailing away. It is nursing time, and they are begging, Quick, give me milk. When provided with a nursing bottle, they begin avariciously sucking. The mixed-blood children, the war produced. Among the numerous misfortunes the war produced, [for] this misfortune that will always afterward remain, the war will not bear responsibility. These very young lives, which will grow in this country where aversions to hair [with a bad lie] [= prejudice] is most fierce (毛嫌いの最も激しいこの国 kegirai no mottomo hageshii kono kuni), who will protect [them]? The agony of when these children eventually know the color of their own hair and realize the color of [their own] skin, of when, on top of this, they understand that they are children without parents, can be imagined. Do the fathers of these children have no sentiments whatever? According to Kōjien, 毛嫌い (kegirai) signifies a dislike of something for no reason, in the sense that an animal likes or dislikes an opponent simply because of the like of its hair (毛並 kenami). |

Stories

Forthcoming.

Yūshū jinsei

Chō Kakuchū 1938

Forthcoming.

Waga fūdokiChō Kakuchū 1942張赫宙 Chō Kakuchū This copy, in Yosha Bunko, has a stamp reading "Kimura Bunko" (木村文庫) on both the front cover and the title page. I am unable to determine which of several so-named collections this volume might have once been part of. The short and long pieces in this collection, on numerous subjects related to Chōsen and its people, were written over a period of years. Some pieces are dated, but their dates -- as early as 1935, as late as 1940 (discounting the afterword) -- do not determine their order. The undated title essay starts and ends with the following paragraphs (pages 9-16).

Chō refers to a number of his works in the introductory essay. Apparently the novel An Idiot's Pure Land (or perhaps it should be "Pure Land for Dummies"), published by Akatsuka Shobō in 1939, was first serialized in the Fukuoka Daily News (福岡日日新聞). Several pieces about Manchuria, including one about Chosenese migration to different parts of the region, are dated 1939 and 1940. The last five essays -- all concerning the past, present, and future worlds of Chōsen literature -- all bear 1940 dates. The afterword -- which Chō titles "After record" (後記 Kōki) and dates January 1917 -- reads as follows (pages 234-235). "Fudoki" (風土記) is the title given later to a gazetteer of localities in Japan written mainly in kanbun after its compilation was ordered by the court in 713. A gazetteer was written for each province on the court's dominion. Only the Izumo no Kuni Fudoki (出雲国風土記) survives nearly complete, while only the Harima, Buzen, Hitachi, and Bungo no Kuni Fudoki (播磨国風土記、肥前国風土記、常陸国風土記、豊後国風土記) partly survive in manuscript form. Parts of the records of some other provinces survive through citations in later works, but the those of most provinces have been entirely lost. |

Buraku no nanboku senChō Kakuchū 1952-4張赫宙 Chō Kakuchū "Buraku no nanboku sen" is sandwiched between stories by Hino Ashihei (火野葦平 1907-1960) and Ūoka Shōhei (大岡昇平 1909-1988), and Chō Kakuchū is otherwise in the company of many of the top writers of the day. His story is one of four stories featured in the largest font in the table of contents. The story is set in neighboring Chōsen villages which had been divided by their own "national border" before the peninsula was split at the 38th parallel after World War II. It begins, though, with a jeep ride to the villages from Pusan, through territory which had fallen to the North Korean army when it attacked South Korea in June 1950, then been reclaimed by United Nations forces, mostly South Korean and American units, in their counter-offensive that fall. The countryside is still raw with the wreckage of a war still raging somewhere further north. The story opens with its teller in a jeep driven by Master Sergeant Kim (金上士), whose job was also to protect him. The road is full of shell holes and the driver is constantly trying to avoid them. A bridge has been destroyed and they have to cross the planks of a temporary bridge running along some small boats in the river. The man sees some refugees in shacks around the girders of the twisted bridge. A middle-age man in a white bachi (朝鮮袴 バチ) is smoking a long pipe. A tomb marker reads "Grave of North Korean officers and troops" (北鮮軍将兵の墓). Something is written below this in English, but the jeep has passed before the man can read it. The driver explains that it was erected by UN forces. The story breaks to the second scene. Further upstream, the man gets out of the jeep, approaches the bank, and gazes across the water. He can see a chapel on a hill. "The church is okay," he inadvertently shouts. Maybe the Chons (全氏チョン) of his Chitenri (知天里ちてんり) have been spared the atrocious punishments of the North Korean army, he thinks. He had read numerous reports in Tokyo of the massacres of followers of Christ. The village [hamlet] (部落 buraku) of Chitari (知太里) had been entirely destroyed. Eighty percent of the villagers (部落民 burakumin) had been believers. Ninety percent of them were members of the Chon clan (全氏一族). Chitari, and neighboring Shinkori (新興里) of the Yun clan (尹ユン一族), had long been mortal enemies. The narrator, Chon, had been accused by Shinkor's leader Yun Choksun (尹赤春 K. Yun Chōksun) of being a reactionary (反動). The pine woods between the two villages had become their national border (国境). The 38th parallel, in Chon's village, had already had a long history of establishment. Chon's eyes fix on a bluff. He cannot see the houses of Chitenri village, as they are obstructed by countless hillocks (丘陵). He thinks of Aemyon (愛蓮 K. Aemyŏn, J. Airen), Choksun's younger sister. Love with a reactionary was not allowed. Even to meet secrety, which was forbidden, would have attracted attention. A marriage alliance was made with another family and she was confined to her own home. Chon, unable to bear the sight of Aemyon being pulled toward the groom's home, sneaks through the darkness up to the sleeping chambers where they would be spending their first night, whistles, and waits. When he knocks on the wall, the door opens, and Aemyon falls into his arms. She appears to have not yet disrobed.

Thus ends the second part of the story (page 169). Chon's adventures begin from the next part, when the jeep reaches the villages and he begins to encounter the past he had left when leaving for Japan. The epilogue begins like this (page 186).

|

|||||||

Aa ChōsenChō Kakuchū 1952-5張赫宙 (著者) Chō Kakuchū (author) Forthcoming. |

Aru hanzaiChō Kakuchū 1952-6張赫宙 Chō Kakuchū This issue of Bungei is Part 1 of "Fifty years of Japanese literature" (日本文學の五十年1). "Aru hanzai" is one of three stories featured under the theme of "War, oppression, resistance" (戦争・弾圧・抵抗). Forthcoming. |

|||||

Pusan no onna kanchōChō Kakuchū 1952-12張赫宙 Chō Kaku Chū "Pusan no onna kanchō" is one of the four documentary short stories featured in this issue. The issue includes a dozen other short stories, several by writers still read today like Kawabata Yasunari and Niwa Fumio, and Fukuda Tsuneari's translation of Ernest Hemingway's The Old Man and the Sea. Umeko, moving her eyes over the people sleeping in the temple, could not believe there was spy among them. Someone in their sleep shouted Help me. Over 300 women and children were illuminated in the moonlight that stole into the main hall. Too bad the lights powered by an American generator had to come on, for in the present case, more than by artifical light, they were saved by the light of the moon. It was a full moon, of the fifteenth night of middle autumn [late summer]. Umeko recalled her youth. Born in Pusan -- where local people practiced o-bon on the old [lunar] calendar in concert with the custom in the Interior (内地 Naichi) of greeting by displaying pampas grass -- Umeko was happy in having been able to receive treats with the Chōsen girls nextdoor. The 320 dead in their sleep, just like in a drawing of hell, stirred awake and began talking. "Pease return me to Japan (日本 Nihon) without a day's delay." "I'm seeing a dream of the Interior. Break my bones so when my eyes open I won't be disappointed." Umeko looked through the documents. Permission to return to Japan had come down for thirteen people in five families. The joy of the five mothers, when they had been told that they could return to the Interior as soon as there was a boat, resounded again in her heart. The women, who had lost their Korean (韓國人 Kankokujin) husbands, even if they remained in this country where they had become total strangers, had no means of living.

The plot, of course, thickens, and the action heads in new directions. |

||||||

KyōhakuChō Kakuchū 1953-3張赫宙 Chō Kakuchū "Kyōhaku" is the first featured of five novellas in this issue -- or "medium stories" (中篇小説 chōhen shōsetsu) as opposed to "short stories" (短編小説 tanpen shōsetsu) or "long stories" [full-length novels] (長編小説 chōhen shōsetsu). The blurb by the title on the Contents page describes the story as "a lonely tale in which a Korean intellectual (韓國知識人 Kankoku chishikjin) who can speak only Japanese endures numerous subtle threats after liberation". Forthcoming. |

|||||

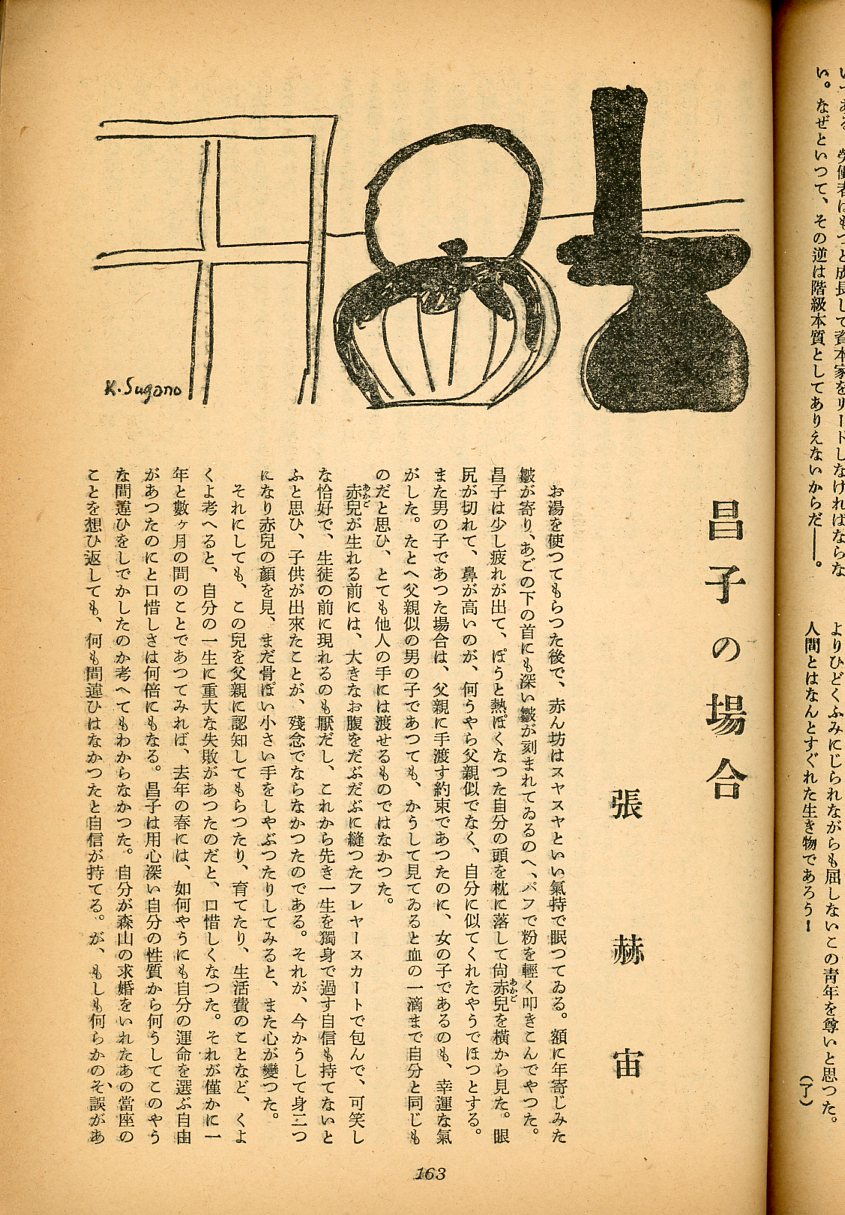

Masako no baaiChō Kakuchū 1953-8張赫宙 Chō Kakuchū "Masaki no baai" is one of 14 short stories featured in the summer reading anthology. The baby, still red and wrinkled, was sound asleep after its bath. Masako, having powering it with a puff, dropped her head to a pillow and looked at the baby from its side. In that its eyes were sharp and its nose was high, it somehow resembled not like its father but her, which relieved her. She had promised that in case it was a boy she would hand it over to its father, but luckily it was a girl. Even it it had been a boy, to see it this way, and think that even one drop of its blood was the same as hers (血の一滴まで自分と同じもの chi no itteki made jibun to onaji mono), she could not have passed it to the hands of someone else. |

|||||

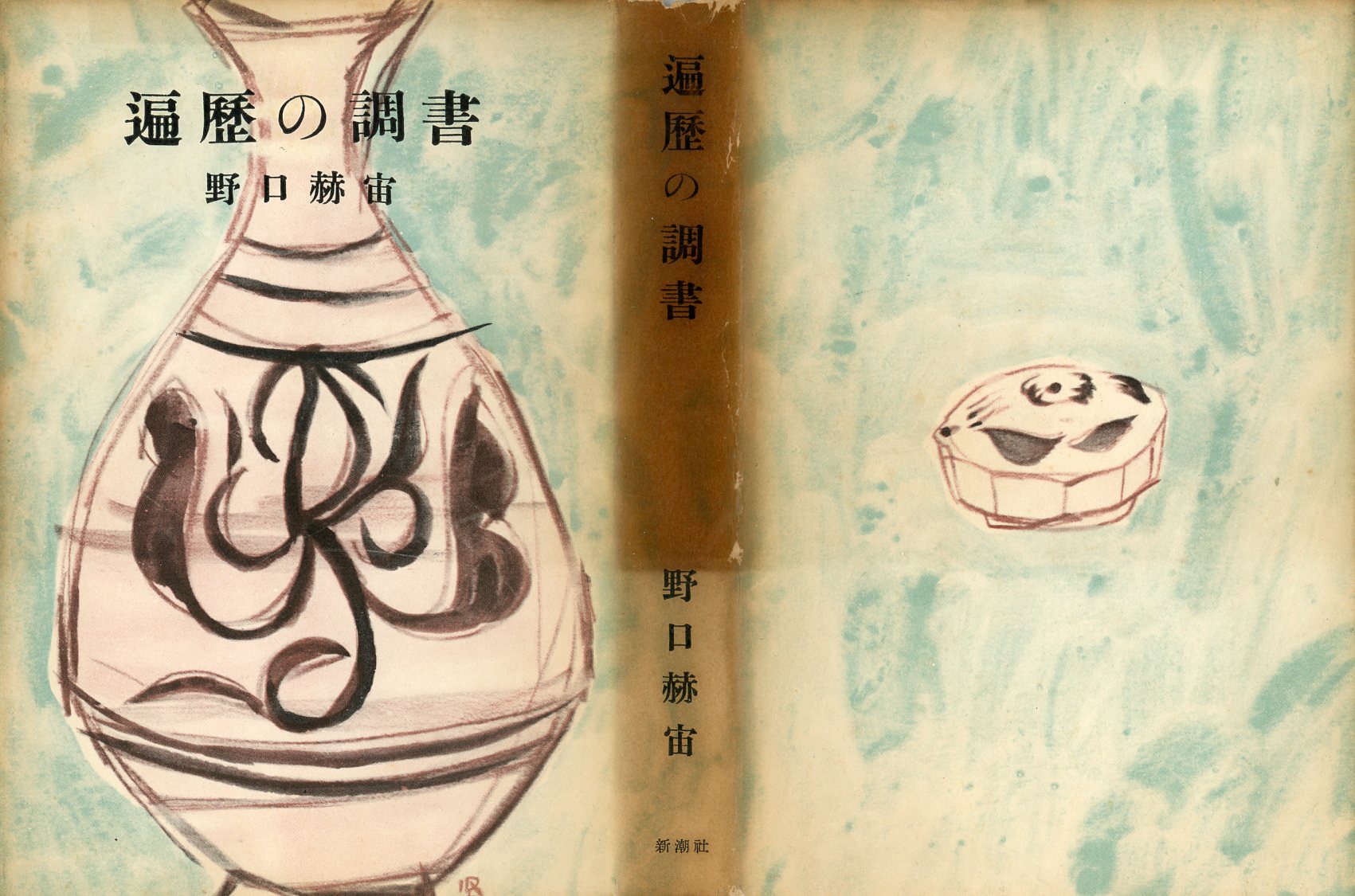

Henreki no chōshoNoguchi Kakuchū 1954野口赫宙 Noguchi Kakuchū This novel is very close to being an autobiography. It certainly invites use as a source for facts about Chō's own life, but here one must be careful. It does, however, qualify as one of several works in which Kakuchū, whether as Chō or Noguchi, explored the psychological and social implications of his own complex life in Korea, in Chōsen and the Interior of Japan after Korea was annexed to Japan as Chōsen, and in Japan after World War II. The story opens with the protagonist "I" (私 watashi) hearing skylarks in the distance, but looking for them, he sees only a few clouds in the glare of the sun. Though his thoughts have drifted, he cannot ignore the existence of Keiko, who is with him, and urging him to return. He tells her he will think about it on his way to where he is going. He looks at Keiko. Her face, puffy from crying all night, looks haggard. "Are you going be happy separating from me and the children?" she asks him. "You're the one who spoke of separation," he tells her. But seeing the tears flood her eyes, he is staggered by his own cruelty. (Page 3) Pages later he recalls his first encounters with Keiko (page 40). She had heard from the maid at the lodging house where he was staying that he was a poet. Having heard of him, she immediately read his poems. Some she found dark, but others were bright. They were unlike her image of him, and he had stuck in her heart. "Just like thorn, right?" he says when she tells him this. He tries to get her out of his mind but can't. One thing led to another (page 41).

|

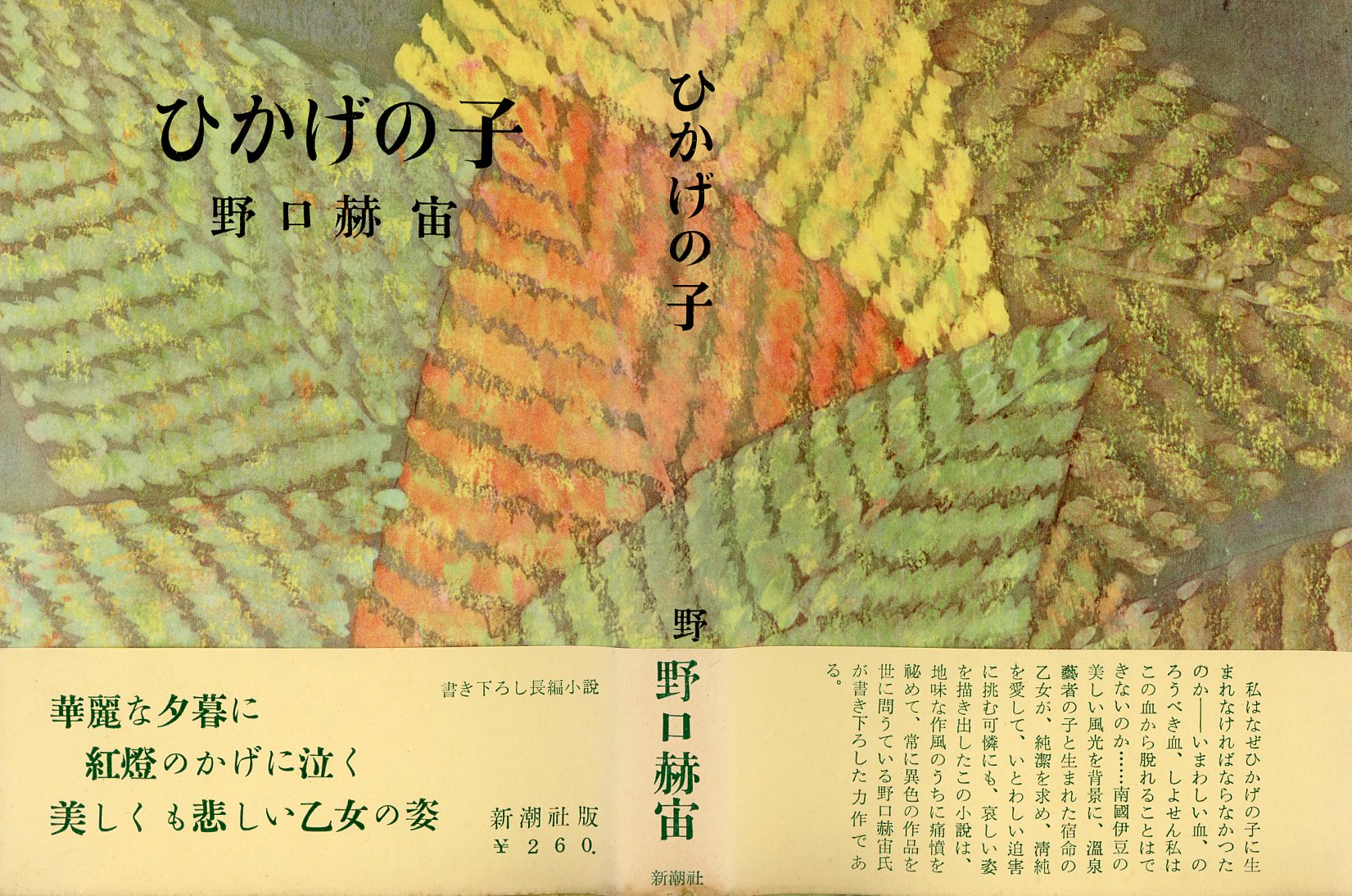

Hikage no koNoguchi Kakuchū 1956野口赫宙 Noguchi Kakuchū Front of obiOn a magnificent evening Back of obiWhy did I have to be born a child of a shadow, why can I not at all escape from this blood, loathsome blood, blood to be cursed . . . . [making] the beautiful setting (美しい風光 fūkō) of Nangoku Izu [its] background, this novel -- which has depicted a touchingly sorrowful figure [picture] in which a maiden whose fate was to have been born the child of a hot springs geisha seeks purity, loves innocence, and defies detestable persecution -- is a powerful work which Noguchi Kakuchū, who is always sending to the world [publishing] different-color [uncommon] works, has written, secreting [hiding] [strong] indignation in a quite style. |

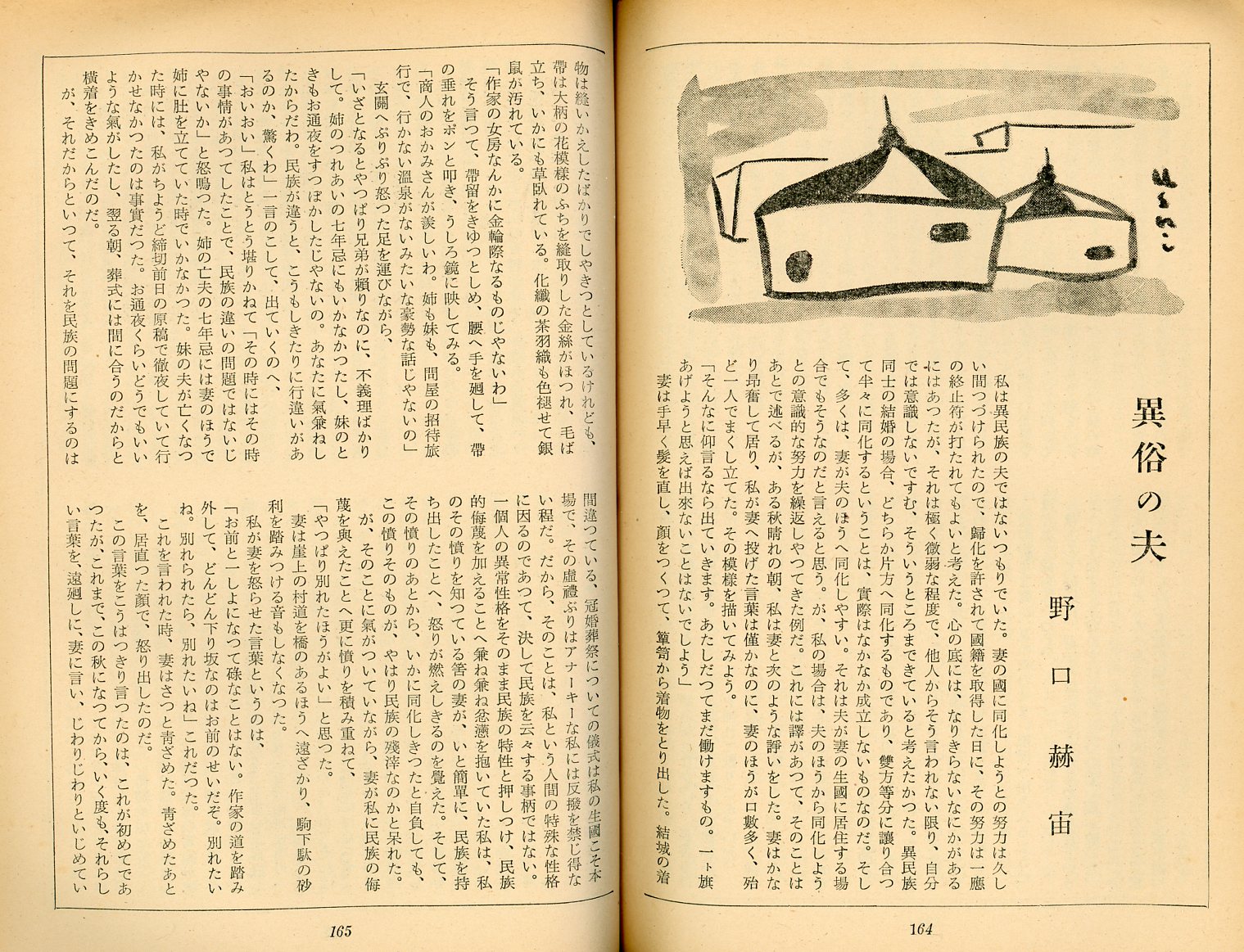

Izoku no ottoNoguchi Kakuchū 1958-5野口赫宙 Noguchi Kakuchū "Izoku no otto" is one of four short stories featured as "medium-length minor-stories" (中篇小説), but they are not quite the length of what would be called "novellas" in English. The other three stories are by Inoue Yasushi (井上靖), Fujiwara Shinji, and Kaikō Ken (開高健). The names of numerous other bundan illuminaries, such as Mishima Yukio (三島由紀夫) and Ūoka Shōhei (大岡昇平), also stud this fairly typical issue of Shinchō. The blurb following the listing of "Izoku no otto" in the table of contents is interesting (my transcription, romanization, and translation).

The story opens with this scene (page 164).

An English version of Noguchi's story appears in Into the Light, an anthology of "literature by Koreans in Japan" edited by Melissa Wender (Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, 2011, pages 66-91). The translation and introduction are attributed to Nayoung Aimee Kwon. For a review of the anthology, see Wender 2011 Kwon, an assistant professor in the Department of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies at Duke University, has retitled Noguchi's story "Foreign Husband" and otherwise heavily rewritten it. She breaks his first paragraph into three parts, and changes his phrasing and metaphors like this (page 68).

This is a good example of what happens too often in translations undertaken by people who set out to retell a story in language they think will be more understandable or appealing to an English reader. The result, here, is not a translation of what Noguchi wrote in Japan in 1958, but an interpretation of what Kwon wants readers to think he wrote, into the language that she and others speak half a century later in America's multiculturalist classrooms. In her introduction to Noguchi's story, Kwon says "izoku no otto" means "man of different customs" -- though "otto" is clearly "husband" (page 66). She also says "iminzoku no otto" is a "play on words" used to mean "foreigner" or "foreign husband" -- though it is nothing of the sort (pages 66-67). The expression very clearly means "husband of a different nation" -- or "husband of a different race" -- either of which would imply nationality" if "minzoku" is rendered into English as it is in the People's Republic of China in reference to racioethnic affiliation. Kwon continues her linguistic analysis like this (page 67).

However, there is nothing problematic about "minzoku" -- a perfectly common word meaning "volk" or "ethnos" or "nation" or "race" in the common racioethnic anthropological sense of these terms when referring to a people who share the language, mores, and customs that define the mainstream population of a country rgarded as a racioethnic nation. Nor is there anything "problematic" or "uneasy" about "race" or "ethnicity" in English when these words are used with their conventional meanings in the conventional writing of conventional writers. Noguchi's use of "minzoku" was entirely conventional. No reader would have viewed his usage as "problematic". He was not equating "minzoku" with a state or its civil population. He very clearly talks about a "country" and its civil "nationality" (kokuseki) apart from "minzoku" as a society of people who share like customs. Though in her introduction Kwon says she will render "minzoku" as "race" or "ethnicity", she does not do this when the word is compounded. According to her glossary, "iminzoku" should mean "different race" or "different ethnicity". But she conflates the first instance of "iminzoku" with "izoku", both of which she morphs into "foreigner" -- and entirely different metaphor. The second instance of "iminzoku" gets morphed into a "mixed marriage" metaphor. Certain "minzoku" would not mean "ethnicity" since at times Noguchi uses the term which might mean this -- "minzokusei" -- and in ways that might also mean "nationality" as ethnic "raciality". The term "minzokusei" had a long history of usage in which it meant "national [ethnic, racial] character" or "nationality" in the racioethnic sense of the word, as opposed to civil nationality. Kwon distorts all manner of phrases in the story. Here she takes Noguchi's use of "blood" to mean simply "blood" for "blood" as a synomym for "ethnicity" (Noguchi 166, Kwon 70). Noguchi 圭子が私の血の民族性を問題にしない・・・ Structural Keiko didn't make an issue of the ethnicity of my blood . . . Kwon Keiko didn't make an issue of my ethnicty, my blood. She does this again a few lines later in a sentence in which the progratonist is expressing the extent of his anger at a policeman who has cast racial insults at him (Noguchi 167, Kwon 71). Noguchi が、私は、「半島の者」呼ばわりをされ、「不逞鮮人」扱いされたことに對しての•懣に、五體が震動するようで、もし權力が私に在つたら、私服の口を八裂きにしてやりたい激怒に目がくらんだ。私は、うしろに居る圭子へ私の血の民族性に異常に拘つた。 Structural But, as my whole body was trembling, with indignation toward having been called "peninsula yokel", and gotten the "unlawful korean" treatment, my eyes were dizzy with a rage that wanted, if the authority had existed in me, to rip the mouth of the plainclothes apart. I, toward Keiko who was behind me was unusually restrained by the ethnicity of my blood toward Keiko, who was behind me. Kwon My entire body was shaking furiously at this man's attitude. He had labeled me a "damn Korean from the peninsula" and treated me like a so-called rebellious Korean. I was so blinded by anger that if I could have gotten away with it, I would have torn him [the policeman] to threads. He made me feel obsessively self-conscious about what Keiko might be thinking about my ethnic blood. Kwon on NoguchiKwon writes that "Chang Hyŏk-chu (Noguchi Minoru/ Noguchi Kakuchū, 1905-1997) was born in colonial Korea". In fact, Noguchi Kakuchū (1905-1997) -- alternatively Noguchi Kaku Chū, legal name Noguchi Minoru, former pen names Chang Hyŏ Chu and Chō Kakuchū -- was born Chang Ŭn Jung (Chō Onjū) in the Empire of Korea. Chang aka Chō (before he became Noguchi) was not a "colonized writer" but a writer who happened to be a subject of Chōsen, as the Empire of Korea was renamed when annexed by Japan in 1910. As such, Chōsen was part of Japan. Chang did not come to did not come to Japan. Japan came to him, and he allowed himself to be embraced. Kwon makes a number of other shakey statements about Chang's life. The most egregious is this (page 66).

Chang took up with the woman that he later married shortly after he migrated from Chōsen to the Interior in the 1930s. He had started his family with her -- five sons according to his biographers in Japan -- long before the end of World War II. His first three sons by Noguchi Hanako -- aka as Keiko, graphically different than the Keiko in the story -- were born in 1938, 1940, and 1942. Chang became Japanese, as did all Chosenese, when the Empire of Korea was incorporated into the Empire of Japan as Chōsen in 1910. He remained a Japanese national until 28 April 1952, when all Chosenese and Taiwanese lost their Japanese nationality in the eyes of Japanese law. He then applied for permission to naturalize, and was permitted to do so by October 1952, according to his biographers and other evidence. He is thought to have authored some works of juvenile fiction in 1949 as Noguchi Minoru, which is possibly the name he adopted on his Chōsen register in 1942. Of some interest is this statement at the end of the first part of the story following the introduction -- though Kwon does not show the break.

|

|||||||||||||||||

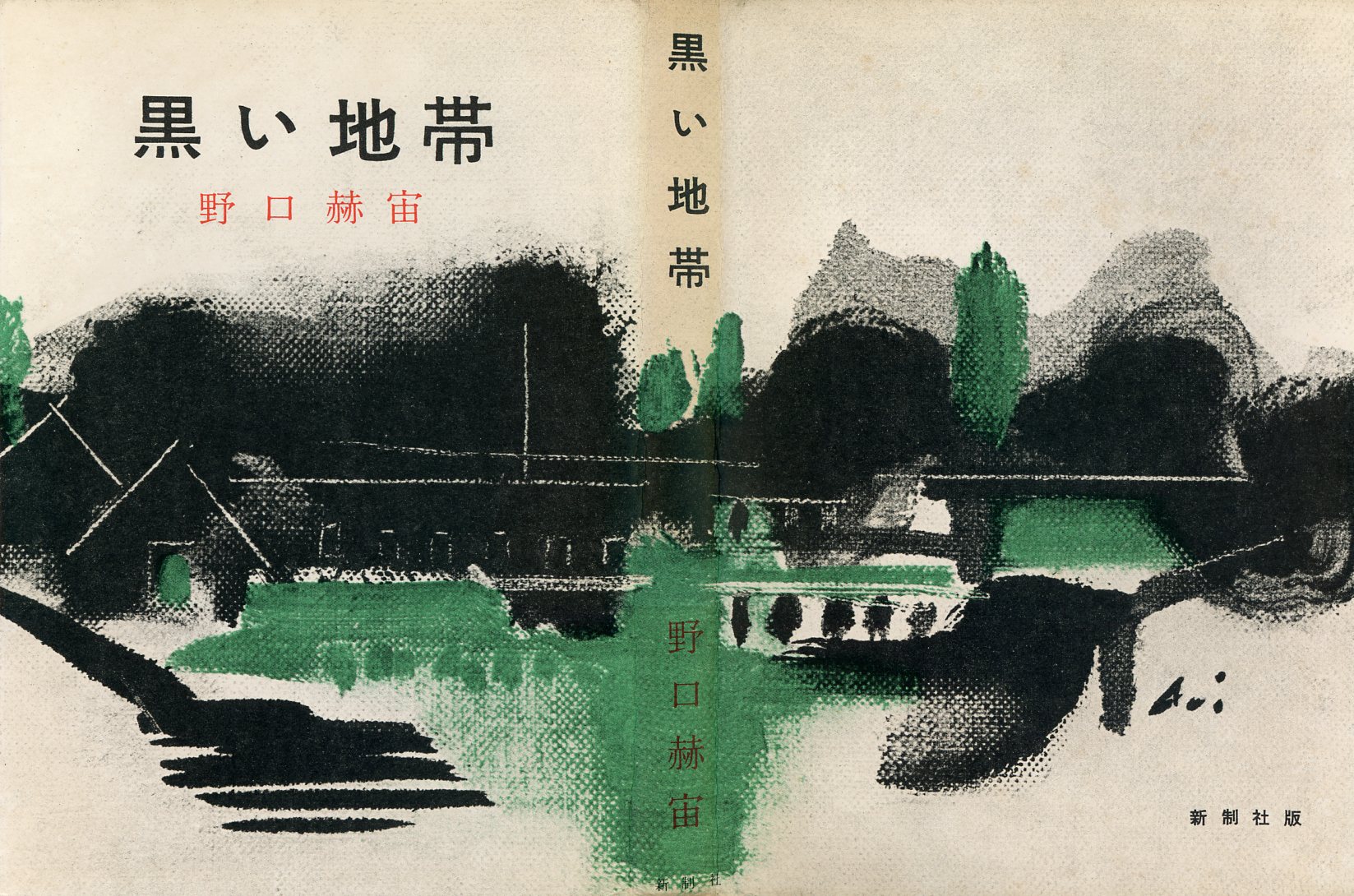

Kuroi chitaiNoguchi Kakuchū 1958野口赫宙 Noguchi Kakuchū The copy shown here includes a printed presentation slip stating that publisher would appreciate any opportunity the recipient might have to review the book. In five titled parts, the novel relates, in an intimate third person, the experiences of Shima, a man who has been told he has tuberculosis that has spread to the point he cannot remain at home but must spend a few years at a sanatorium. He is determined to get well and return to Yukiko AfterwordNoguchi explains the title of the story in an afterword dated August 1958 (pages 333-335). People diagnosed with tuberculosis are left to live in a "black zone". For even if their treatment is effective and they are discharged from a hospital, very few places of work will welcome them. Big comanies, the famous work places protect the "white zone" by not employing anyone with any black spots on their x-rays. "They have to create a 'white zone' by subjugating this 'black zone'" (page 334). Noguchi wrote the novel because he discovered that tuberculosis was not quite -- as he had come to believe, along with many others at the time -- a disease that was no longer to be feared. Cancer may have become the disease everyone had come to fear -- and the disease he had begun to study -- but tuberculosis was still a continuing problem for many people. In 1959, the year after Kuroi chitai was published, Kōdansha brought out Noguchi's Gan byōtō (ガン病棟) -- "Cancer ward" -- which see next. |

Gan byōtōNoguchi Kakuchū 1959野口赫宙 (のぶちかくちゅう) Noguchi Kakuchū <© Kakuchū Noguchi> In this novel, Noguchi does for cancer what he did for tuberbulosis the year before in Kuroi chitai (see above). This time, though, the protagonist is a nurse who tells, in her own voice, in four separately titled parts, what transpires on and off the cancer ward of a large hospital and an annexed research institute -- from the smell of formalin and cresol, the pH of gastric juices, the examination of tissue from from surgically removed tumors, to diaper changing, and the suffering of cancer patients and their loved ones. And what medical novel would be complete without romance and rivalry among and between doctors and nurses? |

Kojō no fushichōNoguchi Kakuchū 1962野口赫宙 Noguchi Kakuchū (© Kakuchu Noguchi) Endorsement on front flap of jacket by the novelist Inoue Tomoichirō (井上友一郎 1909-1997). Author's afterword dated January 1962. Forthcoming. |

Juvenile fiction

Forthcoming.

Chō Kakuchū juvenile titles in NDL database

The database of National Diet Library's International Library of Children's Literature (国立国会図書館国際子ども図書館) attributes the following three works -- published in 1942, 1948, and 1949 -- to Chō Kakuchū (張赫宙). I have somewhat edited and reformated the descriptions, and of course the romanizations and translations are mine.

The database equates Chō Kakuchū with Noguchi Kakuchū (野口赫宙), and shows "1905-1998" as his birth and death dates. Shirakawa's chronology of Chō's life states that he died at a hospital near his Saitama prefecture home on 1 February 1997 (Shirakawa Yutaka, in Chō 2003, page 341).

張赫宙 (著)

フンブとノルブ

東京:赤塚書房, 昭和17年

225ページ

Chō Kakuchū (author)

Mikami Shinji (drawings)

Funbu to Norubu

[Funbu and Norubu]

Tokyo: Akatsuka Shobō, 1942

225 pages

張赫宙 (著)

やまめ釣る子

東京:講談社、昭和23年

261ページ

Chō Kakuchū (author)

Yamame tsuru ko

[A child (boy) who fished for yamame (trout)]

Tokyo: Kōdansha, 1948

[ 大日本雄弁会講談社 Dai-Nihon Yūbenkai Kōdansha ]

261 pages

張赫宙 (著)

三上信次 (絵)

恩を返したツバメ

東京:羽田書店, 昭和24年

230ページ

Chō Kakuchū (author)

Mikami Shinji (drawings)

On o kaeshita tsubame

[The sparrow that returned benevolence]

Tokyo: Haneda Shoten, 1949

230 pages

Funbu to Norubu is based on a popular Korean folk tale called "흥부와놀부" (Hŭngbu wa Nolbu), about two brothers -- Funbu (Hungbu) the younger, poorer, and kinder -- and Norbu (Nolbu) the older, richer, and greedier.

Noguchi Minoru juvenile titles in NDL database

The same National Diet Library International Library of Children's Literature database attributes the following three works of juvenile fiction, published in 1949 and 1950, to a Noguchi Minoru (野口実).

The database does not equate Noguchi Minoru with either Noguchi Kakuchū or Chō Kakuchū.

野口実 (著)

玉井徳太郎 (絵) [1902-1986]

異国の嵐

東京:偕成社, 昭和24年8月30日 (発行)

224ページ

Noguchi Minoru (author)

Tamai Tokutarō (drawings)

Ikoku no arashi

[Storm of [in] a different country]

Tokyo: Kaiseisha, 30 August 1949 (published)

224 pages

野口実 (著)

原研児 (絵)

港の聖花

東京:偕成社, 昭和24年

246ページ

Noguchi Minoru (author)

Hara Kenji (drawings)

Minato no seika

[Sacred flower of the harbor (port)]

Tokyo: Kaiseisha, 1949

246 pages

野口実 (著)

花房英樹 (絵)

流れの旅路

東京:偕成社, 昭和25年

279ページ

Noguchi Minoru (author)

Hanabusa Hideki (drawings)

Nagare no tabiji

[Journey of [like] a flow (current, stream)]

Tokyo: Kaiseisha, 1950

279 pages

Kanda book dealer's story

A Kanda book dealer who sells mainly through catalogs and on-line told me an interesting story. He specializes in Meiji, Taisho, and early Showa works and is especially strong on the history and literature of these periods. His store is not a shop but an office with stacks on the fifth floor of a ferro-concrete building a couple of blocks off the main street. The stacks, on rails behind his own desk and that of an assistant, are not set up for walk-in trade, and he and his assistant, whose desks are immediately in front of the entrance, were not expecting me.

The dealer listened to my requests while consulting his memory and well-thumbed ledgers crammed with hand-written entries. He asked his assitant, who appeared to be in charge of the computer, to run Kakuchū through the store database. She has heard our conversation and knows the author we are talking about but has to be told that the character for "kaku" is the one for "two reds without the mouth radical". She fulls down the entire list, consisting of about two dozen volumes -- most very pricey.

I had gone to the dealer to buy two or three of the cheaper titles and examine a copy of Minato no seika. At 129,000 yen, it was the most expensive volume, but the dealer allowed me to examine it, among several others he knew I didn't intend to buy, and shared some interesting information with me.

The dealer had represented Minato no seika as having been written by Noguchi Kakuchū (野口赫宙), which was at odds with the NDL listing. The cover, title page, and colophon of his copy, though, showed that it to be the work of Noguchi Minoru (野口実). I remarked that the graph for Minoru was written with what is called the "shinjitai" (新字体) or "new [simplified] font" of form of the graph. Such forms, adopted in 1949 as the standard forms, were not really "new" but represented cursive or semi-cursive abbreviations of fuller forms, which had been recognized for use in 1923 and 1946 reforms. The dealer remarked that, at the time, 実 (mi, minoru, makoto) was considered the "zokuji" (俗字) or "popular [customary] graph" for 實, which is now called the "kyūjitai" (旧字体、舊字體) form.

I then asked why this was not the "nogihen" Minoru (稔) that Chō later adopted as his legal name when naturalizing in 1952. And as soon as I said "nogihen" the dealer opened his mouth. But he waited until I had finished my sentence to tell his story about the name.

He knew there were a couple of other titles in the Kaiseisha series but hadn't seen them. He said, though, that he had spoken with Noguchi's son a number of years ago, about the titles, and was told by the son that his father had used Noguchi Minoru during the Occupation because he had been receiving threats from other Koreans in Japan who regarded him as a traitor.

This did not, however, account for the fact that, throughout the Occupation of Japan, not only had Chō published numerous books, stories, and articles under the name Chō Kakuchū, but continued he continued to write under this name for a year or so after he had Noguchi Minoru (野口稔). And even then, he continued to use Kakuchū with Noguchi as his penname.

I told the book dealer that the NDL database showed three juvenile titles by Chō Kakuchū, two of which were published by Kōdansha and Haneda Shoten during the period that Kaiseisha was publishing titles by Noguchi Minoru. The dealer knew the name of one of the titles, and offered that possibly they they were reissues of postwar editions published without the author's permission, as was not uncommon at the time, he said.

I had been looking at the colophon of Minato no seika, and the dealer, and jotting down its particulars. The dealer then drew my attention to advertising in the back of the book, which listed other titles in Kaiseisha's juvenile fiction series. All the authors, he said, were established writers of "jidōmono" (児童物) or "children's literature".

Of interest here is that NDL's children's literature database has no other titles attributed to "Noguchi Minoru" no matter how it is graphed. And I find no other references to an author of children's books of this name.

Noguchi Kakuchū is attributed as the translator of several "Chōsen [Korea] children's tales" (朝鮮童話集 Chōsen dōwa shū) collected in Volume 25: Chōsen 1 (1954) and Volume 43: Chōsen 5 (1956) of "Complete works of world literature for young boys and young girls" (世界少年少女文学全集 Sekai shōnen shōjo bungaku zenshū) published by Tōkyō Sōgen Sha (東京創元社).

Somewhat oddly, the NDL juvenile database lists Kuroi chitai (1958), which is anything but a work fiction for the children's literature market.

History triology

Forthcoming.

Kara to WaNoguchi Kakuchū 1977野口赫宙 Noguchi Kakuchū Later in his life, Noguchi was inspired by studies of early civilizations to write his own contribututions to the ongoing discussion of the origin of Japan and its people. Kara to Wa explores the commonalities of Mongoloid peoples and the puzzle of the country of Wa in early times (Part 1). It also examines the "facts among the myths" surrounding the descent of Emperor Jinmu and the "Heavenly-grandson race" (Tenson minzoku 天孫民族) established by the descent to earth of Amaterasu's grandson Ninigi, who was Jinmu's great grandfather (Part 2). Kara to Wa also delves into blood ties between Yamato (Wa 倭) and Korea (Kara 韓), especially links between Emperor Sujin and the southern part of Chōsen (Nansen 南鮮) (Part 3).The book concludes with a the transition from "Wa" to "Japan", during the period of fighting with Kokuri (高句麗 Koguryŏ), when Yamato adopted Buddism through mostly Kudara (百済 Paekche). Yamato withdrew from the peninsula when Kudara forces and allied Yamato forces were defeated by Silla forcea, after which Yamato became Japan. Sujin and MimanaNihon shoki (Chronicles of Japan), Japan's earliest chronology (720), states that during Sujin's reign (before the period when historical confirmation is possible), Mimana (任那 SJ Ninna, SK Imna) sent an envoy to Yamato with tribute (my translation, Nihon shoki 1, NKBT-68, pages 252-253, cf. Aston 1, page 164).

任那國遣蘇那曷叱知令朝貢也。 Five years later, during the 2nd year of Sujin's successor Suinin, the Mimana envoy returned to Mimana with gifts from the Yamato court to the king of Mimana. But en route to Mimana, he was attacked by some people in Shiragi (新羅 Silla), who took the gifts, which is said to have started the animosity between the Korean entities that also embroiled Yamato (Ibid. NKBT-68, 256-257, Aston-1, 166). Mimaki IrihikoSujin's Yamato-style posthumous name is "Mimaki Irihiko" (御間城入彦). "Irihiko" is title which some have translated "prince". "Mimaki" is thought to be a place name. Some people think it means "Mima castle" and claim that "Mima" refers to Mimana, a territory identified with Kaya (伽羅) in the southern part of the Chōsen peninsula closest to Yamato. Some contend that Sujin established suzerainty over Mimana, which is thought to have been at least partly under Yamato control. A few have claimed that Sujin himself came to Yamato from Mimana and was therefore Korean. |

Yakimono to tsurugiNoguchi Kakuchū 1980野口赫宙 (のぐちかくちゅう) Noguchi Kakuchū <© K. Noguchi> The introduction begins with this statement (page 5).

Noguchi observes that this work follows Kara to Wa, which explored the origins of the "descendants-of-heaven race", meaning the ancestors of the Wa or Yamato nation. He contends the Wa race [racioethnic nation] in the islands that became Japan stemmed from earlier migrations of Tungusic peoples from the continent, which added another race to the previously settled races [indigenous races] (先住民族 senjū minzoku). Later came people from various Koreans entities, especially Paekche, both as envoys, migrants, and finally refugees. It was more through relations with Korean entities, and even presence on the peninsula and involvement in its conflicts, and through the settlement in Japan of Korean artisans, literati, and even nobility, that the languages and cultures of Wa (Yamato, Japan) came to be Sinified, and to some extent Koreanized, while remaining Japanese. In Yakimono to tsurugi, Noguchi takes similar pride in the migrations to Japan of a number of Korean potters, provoked by Hideyoshi's military invasions of Korea in the last decade of the 16th century, which lead to the development of Satsuma (薩摩), Arita (有田), Karatsu (唐津), Hagi (萩), and Raku (楽) kilns, among others. In his afterword, dated 1 October 1980, Noguchi reiterates the importance of the "great movements of races" [volkerwanderung] (民族大移動 minzoku dai-idō) described in Kara to Wa, and notes that the migrations in the wake of Hideyoshi's invasions and retreats came about one millennium after the earlier migrations (page 229).

|

Maya-Inka ni Jōmonjin o ouNoguchi Kakuchū 1999野口赫宙 (のぐち・かくちゅう) Noguchi Kakuchū Noguchi concludes his afterword, dated May 1989, like this (pages 236-237).

Noguchi, who claims not to like looking back, is looking back at his own life on the eve of reaching 85, and realizing that he is still alive, well, and active a decade after most of his age peers had passed away. He is proud that his first story, published in a magazine in Chōsen in October 1930, has been anthologized in Volume 3, titled Genjitsu no gishi (現実の凝視 "Gazes of reality"), of a 15-volume work published in 1976-1977 by Ie no Hikari Kyōkai (家の光協会), which collected numerous stories of various writers about local conditions in their home villages and towns. "Owareru hitobito" (追はれる人々) or "People driven away", published in 1932 in the September/October issue of Kaizō (改造), is also included in this volume. Of some interest here is the author blurb on the colophon. I have shown it below beside blurb on the colophon of Yakimono to tsurugi (1980). The latter blurb is the same as the blurb on the back flap of the jacket of Kara to Wa (1977), except that it added this work to the end of its list of representative works, and it dropped the furigana showing that 新羅 (J. Shiragi, K. Silla) is to be pronounced しらぎ.

Noguchi has all but written "Chōsen" out of his past in the 1989 profile, and not because of lack of space. Possibly the publisher wrote the profile and Noguchi just accepted it. No mention is made in either blurb that "Noguchi Kakuchū" wrote as "Chō Kakuchū" until 1954, or that "Chō Kakuchū" -- the penname he adopted when still Chang ŭn Jung (張恩重 SJ Chō Onjū) on his Chōsen register. Chō became legally "Noguchi Minoru" in 1952 (if not earlier). But such details appear not to have been important to him (or his publishers), since by then he was not promoting himself (or being promoted) as a Chosenese or former Chosenese. The phrase "coming to Japan" (来日 rai-Nichi) reflects both the time and place where he is writing -- in Japan in 1989, about eight decades after 1910 when Korea was annexed to Japan as Chōsen, and 45 years after Chōsen was "liberated" from Japan as Korea in 1945. While "coming to Japan" was not an impossible expression at the time Chō "came to Japan" in 1926, most likely he would have said something like "coming to the Interior" (内地に来る Nainichi ni kuru) or "crossing-and-coming to the Interior" (内地に渡来する Naichi ni torai suru). For "Japan" at the time embraced the Interior (prefectures), Taiwan, Karafuto, and Chōsen, and hence going from Chōsen to any of the other three territories would have been traveling within Japan. Moreover, in 1926 Chō had traveled to the Interior as a subject and national of Japan. Born a subject of the Empire of Korea in 1905, he became a subject, hence a national, of Japan in 1910, as a consquence of the annexation. As a subject of Japan from 1910 to 1945, his allegiance was formally to Japan. In Occupied Japan from 1945 to 1952, his status was dual -- at once "Non-Japanese" as a "liberated national" of Korea (referring only to the former Japanese territory of Chōsen), yet also "Japanese" as a former subject of Japan who formally continued to possess Japanese nationality. I say "former subject" because "subjecthood" as a legal status ended the day Japan signed the General Instrument of Surrender, in which it recognized that its sovereignty was in the hands of the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers (SCAP). Chō did not formally lose his Japanese nationality until 28 April 1952 as a consequence of the separation of Korea (Chosen) from Japan under the terms of the San Francisco Peace Treaty. Only then was he able to apply for permission to "change allegiance" to Japan -- i.e., "naturalize" in Japan -- under Japan's Nationality Law. Again, such details do not seem to have mattered. Arguably, as he wrote in 1942 in the introduction to My Record of Wind and Land, "[I] am me" -- though at the time he added "but as for me, among these three [I] belong to the last Silla character" (see above). "Poplars" -- about the sorrows of a Chōsen tenant farmer -- was actually published in the October 1930 issue (Volume 2, Number 10) of the anarchist and agrarianist magazine Daichi ni tatsu (大地に立つ). Pearl Buck's 1931 novel The Good Earth -- the first of her trilogy on three generations of a farming family in China -- was translated into Chinese and Japanese under the title "Daichi" (大地) or "Great earth". |

English translations

At least three of Chō's or Noguchi's works have published in English.

Forthcoming.

Forlorn Journey

The following novel is supposed to be set in 17-century Japan and involve intolerance toward Christianity.

Kaku Chu Noguchi

Forlorn Journey

New Delhi India / Tokyo Japan: Chansun International, 1991

420 pages

The above information is based on a small scan of the cover and accompanying information on Open Library. I have not otherwise seen the book.

Rajagriha

The above work represented on Google Books, which shows the graphs for Noguchi's name on the cover. Another edition is elsewhere represented as having been published in May 1993 by South Asia Books.

Kaku Chu Noguchi (野口赫宙)

Rajagriha

(A Tale of Gautama Buddha)

New Delhi: Allied Publishers Limited, 1992

354 pages

The copyright page of the Allied Publishers Limited edition shows "First published 1992 / © Minoru Noguchi, 1992" (Google Books). Noguchi, while retaining Kaku Chu in his byline, is using his legal name as copyright owner. The colophons of Japanese publications during the two decades before this, however, show "© K. Noguchi" in roman script.

The blurbs on the back cover introduce Noguchi, his work, and the story as follows (Google Books).

|

Minoru Noguchi (pen name Kaku Chu Noguchi) is one of Japan's leading writers. He has written over thirty-five novels, short stories, essays and fairy tales in the Japanese and Korean languages. He also has three works written in English to his credit. Rajagriha is a novel revolving around the lives of two contemporary characters, Ajatashatru (representing all that is evil) and Gautama Buddha. Based on Buddhist and Jain archival material compiled after much arduous research, this is the first English edition of a work originally written in Japanese. |

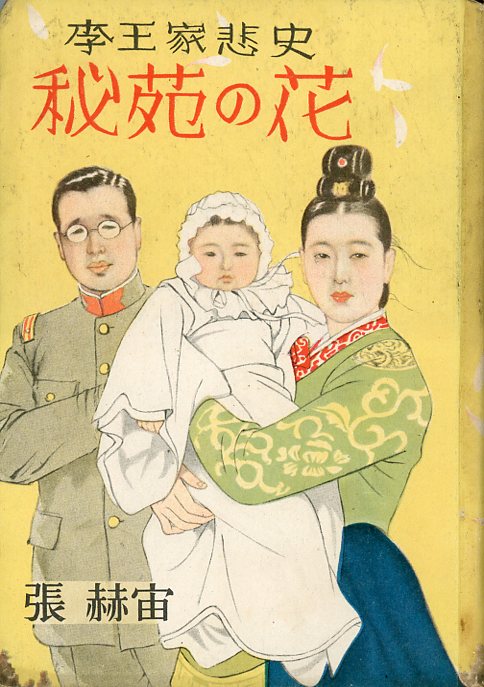

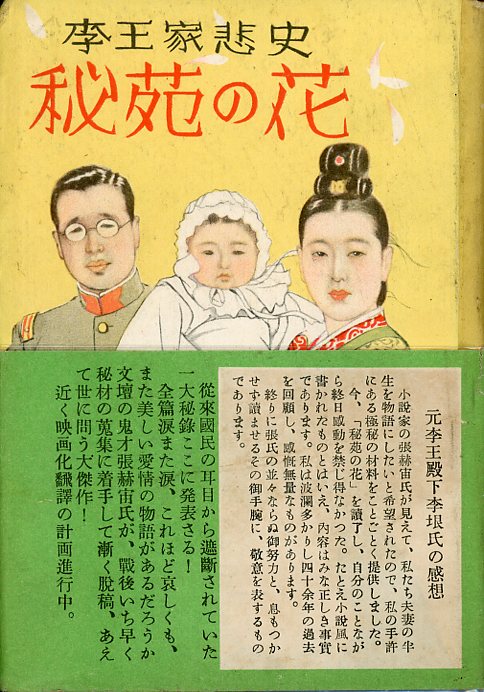

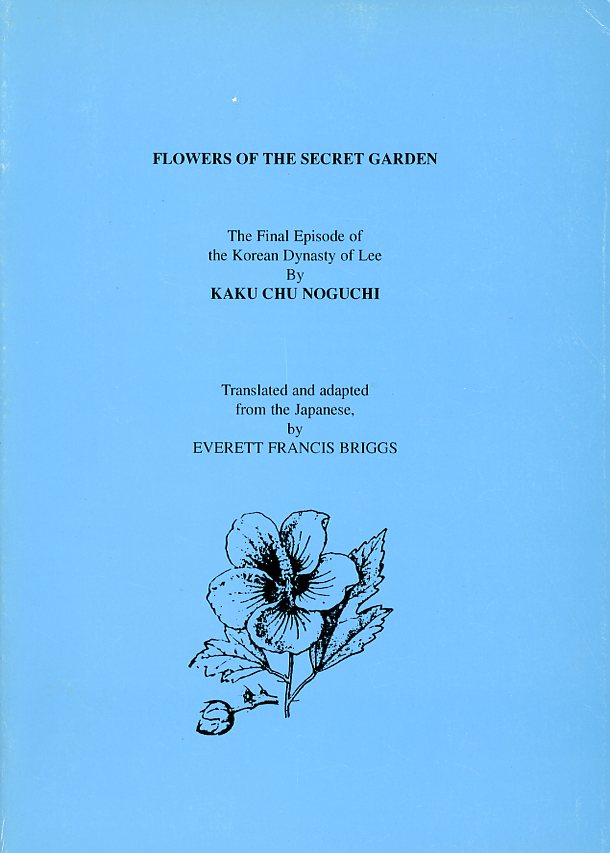

Hien no HanaIn 1950, during the Occupation of Japan and three months before the start of the Korean War, Chō Kakuchū (1905-1997) published a biography about the marriage of the last Crown Prince of the Empire of Korea and a princess of the Japan's imperial family. In 1999, Everett Briggs (1908-2006) published an English translation and adaptation of the biography a work by Kaku Chu Noguchi, a "Koreanized" version of Noguchi Kakuchū, which was Chō's name after he naturalized in 1952. Chō Kakuchi 1950張赫宙 Chō Kakuchū Kaku Chu Noguchi 1999Kaku Chu Noguchi StoryThe story is about Princess Yi Pang Ja (李方子妃 1901-1989) -- or Princess Pangja as she calls herself her 1973 English biography The World is One. In Japan she is known as Ri Masako (李方子) or Princess Masako (方子妃), a daughter of Prince Nashimoto and cousin of Hirohito's wife Nagako. In 1920, Masako married Prince Yi Un (李垠 Yi Ŭn 1897-1970), the seventh son of Kwangmu, the first emperor of the Empire of Korea, and a younger half brother of Sunjong, Kwangmu's fourth son and successor. Yi Un, who stood to succeed Sunjong, is thus considered the last crown prince of Korea before its annexation by Japan as Chōsen in 1910. Members of the defunct Korean imperial family were given honorable titles in recognition of their former royal status. Chō's interest in this final chapter in the "sorrowful history" of the Yi dynasty family centers on the marriage between Un, a member of this family, and Masako, a member of the Japanese imperial family. Their union thus represented a mixed "Interior-Chōsen marriage" (内鮮結婚 Nai-Sen kekkon), and the children they produced were "Interior-Chōsen hybrids" (内鮮の合の子 Nai-Sen no ainoko). The trials of such couples and their children were favorite and even obsessive themes for Chō, who himself, as a Chōsen man, chose to live with, begin a second family with, and eventually marry an Interior woman. See the story of Princess Masako and Prince Yi Un in Ri Ku: A child of a marriage of convenience in the People section of the Konketsuji website. English translation and adaptionThe particulars of the version published by Briggs are as follows (based on copy in my own Yosha Bunko collection). The Foreword is signed "Everett Francis Briggs, Monongah, West Virginia, U.S.A." -- hence some bookdealers represent the book as having been published in Monongah, West Virginia, but the copyright page on the back of the front cover states differently. The title page promotes the story like this (uncerscoring in original).

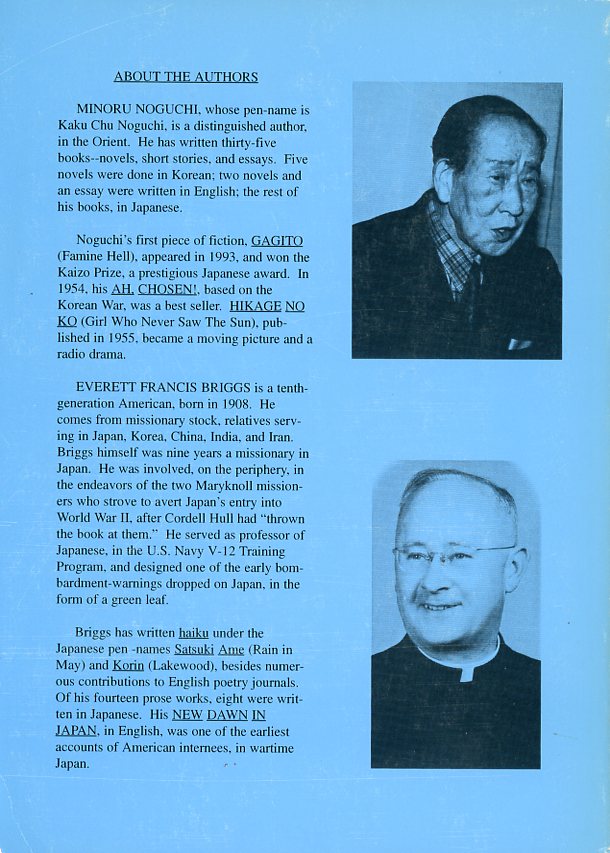

Biographical descriptionsThe back cover -- "ABOUT THE AUTHORS" -- shows portraits and biographical descriptions of both "MINORU NOGUCHI" and "EVERETT FRANCIS BRIGGS" -- with more space allocated to Briggs than Noguchi. The two authors are billed as follows.

Translator's forewordBriggs published his translation and adaptation two years after Noguchi's death. The biographical statement on the back cover, and the following references to Noguchi in the undated Foreword, however, speak of Noguchi as though he were still alive (pages 6-10, underscoring in original).

Lee Eun's introductionThe undated Introduction in the English version is attributed to Lee Eun (1897-1970), who passed away two decades after the original work and about three decades before the English version (page 11).